|

Drama review

Daasa Mallige Bungalawa :

Impressive performances

by Dilshan Boange

Part 2

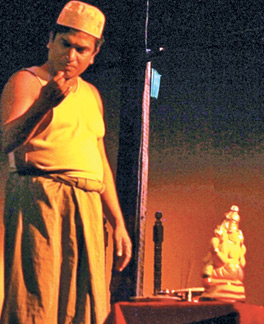

One of the significant aspects that lends to the understanding of the

inner being of Daasa as well as a cultural and psychological premise to

gauge the positions in which the characters are to be found, is in the

arrival of the idol of God Ganesh or ‘Ganapathy’. Lechchami, a Hindu

woman is shown to be extremely religious. However, rituals seem

nonsensical to Daasa. He makes some changes to his daily routine to

please Lechchami. For instance, he joins her in religious rituals. He

thinks that she should consider it a great sacrifice. One of the significant aspects that lends to the understanding of the

inner being of Daasa as well as a cultural and psychological premise to

gauge the positions in which the characters are to be found, is in the

arrival of the idol of God Ganesh or ‘Ganapathy’. Lechchami, a Hindu

woman is shown to be extremely religious. However, rituals seem

nonsensical to Daasa. He makes some changes to his daily routine to

please Lechchami. For instance, he joins her in religious rituals. He

thinks that she should consider it a great sacrifice.

His behaviour shows that there is a need to develop a personal bond

with every woman he brings home to be his housekeeper-cum-companion.

Yet it is within very strict demarcations of disallowing the woman to

become the custodian of the house. What is interesting to note is that

despite the fact that he casts Lechchami out of the house, the image of

Lord Ganesh and the altar of worship continue to exist. But he thinks

that religion is utterly useless.

The late Prime Minister of India Indira Ghandi, in an interview with

a foreign magazine said, “Indians are not a god-fearing people, they are

a god-loving people.” The different gods in the Hindu pantheon allow

devotees to chose any god they prefer depending on their character

traits.

But to Daasa, it all seems juvenile yet tolerable. His understanding

of religion does not involve any ideological underpinnings since he

seems nothing wrong with his best friend Bawa taking part in making the

offerings to God Ganesh when Lechchami strongly opposes it saying that

Bawa is a Muslim and he is disqualified from having a hand in the

ritual.

Adaptation

Based on the fact that the play is an adaptation of an Indian play I

was wondering whether the original also has a protagonist whose attitude

towards the religious devotions of the ‘first female’ is just as

irreligious or was it developed more on the lines as a scenario

depicting a Sinhala man thinking snidely of the religious devotions of a

Tamil Hindu woman.

There is enough evidence in dialogues that Daasa views Lechchami’s

level of religiousness as a trait related to her community since he says

the woman before her was also constantly engaged in acts of professing

devotion which included worshipping a shirt owned by her husband who

cast her out.

A senseless devotion as stated by Daasa which renders women such as

Lechchami a puzzle to him. The manner in which Daasa comments about the

image of God Ganesh also renders him an unapologetically irreverent man.

That ‘premise’ of the triangular connection between Daasa, Lechchami

and Ganapathy is one that allows ‘space’ for much theorisation about the

role religion plays in human relations in Daasa’s abode.

|

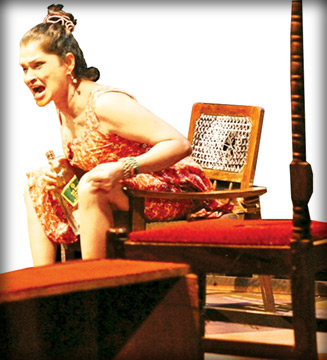

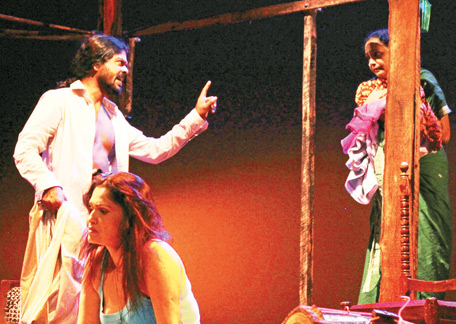

Scenes from the play |

The nature of the characters are such that they are brought to life

to evoke emotions of either empathy or resentment or both. One may say

that Lechchami may not attract censure from anyone, I found her acting

for self survival.

Some characters display attributes that are deplorable. For instance,

Indrapala’s pathetic slavishness to the woman who berates him, or Bawa’s

sneaky opportunism to satisfy his lust with Champika, can be cited.

Politics of laughter

The celebrated postmodern novelist Milan Kundera in his

quasi-biographical novel The Book of Laughter and Forgetting speaks of

the politics of laughter and the manifold significances a laugh can have

in relation to the ‘laugher’ as well as the people who perceive the

laughter.

Laughter becomes a reason for gruesome beatings to happen in the

drama. And how laughter is an objective of many a theatregoer in Sri

Lanka is a topic that must be looked at in the context of this drama.

Lechchami’s friendship with an ant with whom she is discovered

conversing attracts Daasa’s intrigue, bemusement and amusement.

The laughter that he hears coming out of her when talking to the ant

begins to kindle in him a desire to hear that element of ‘femininity’

recurring in his presence.

He shows a desire for it yet when denied it ‘on call’, is persistent

of his demand. When meted with lack of complicity by Lechchami the

result is severe manhandling and brutal power play to depict that he

doesn’t tolerate defiance of his commands, especially if they are

connected to some sensitive aspect within him.

Lechchami’s cries that erupt are a deftly delivered blend of laughter

and wails that blur the lines between tears of laughter and those of

pain. There is irony that is ripe to befuddle the viewer as to whether

she is crying out in jest and humouring Daasa and defeating his

dominance attempted over her sought a belt she is being lashed with, or

whether she is giving cries of laughter that is self mockery at her own

pitiful plight and the existence that is absurd to her? Or is it clear

cut cries of pain?

The answer is perhaps, that it is the flux of these different

emotions within Lechchami finding form as an oral expression. On this

aspect Ravini Anuradha who played Lechchami must be saluted for her

prowess as an actress.

Gestures

There was laughter that erupted from the audience at the threatening

gestures made by Daasa to Lechchami when the former was truculently

demanding the latter to laugh.

Yes, it is absurd to think that someone would make a request like

that and then keep insisting on it.

The demeanour of Daasa as created by Jayantha Muthuthantri at that

moment may make him seem moronic and possibly be seen as an object to

laugh at, but what I experienced to my dismay was that the inability of

many viewers that night to catch on to the significance of those

threatening gestures that were precursors to the violence done on

Lechchami.

Once the belting got underway the laughter died among the viewers,

but it also showed a dimmed sensitivity as to how Daasa’s words, the

gesture and tone could not be seen as the ‘promise of violence’ unless

his orders are obeyed.

That was no laughing matter. At the point when there was that

confusion created through the variance of tone of the cries by Lechchami

to confuse the viewer as to whether she was crying in pain or laughing

sardonically, laughs cropped up from here and there in the audience.

And I was rather disturbed about what those audience reactions

indicated about the people who watch theatre.

Perhaps there is a preconception among most theatregoers in Sri Lanka

that theatre is about a performance purely for enjoyment and that

enjoyment involves junctures that evoke laughter. I wondered whether it

is the influence of sitcoms that may attune a viewer to be cued for

laughter the very moment something seems a bit absurd and amusing. Perhaps there is a preconception among most theatregoers in Sri Lanka

that theatre is about a performance purely for enjoyment and that

enjoyment involves junctures that evoke laughter. I wondered whether it

is the influence of sitcoms that may attune a viewer to be cued for

laughter the very moment something seems a bit absurd and amusing.

Merciless

When commenting on how theatre connects with society and what role

and relevance it has to the community at large as a medium of art that

reflects realities in society as a live performance, I believe what I

experienced offers much food for thought. And what may be reasonably

deduced as to possible reflections of society may be disturbing.

At the point where Lechchami is given her most severe belting, where

she is down on the ground and Daasa’s hand moves in merciless velocity

the stillness in the audience was intense. The crack of the belt against

the wooden boards was like a gag put on the audience.

And as the whipping intensified I actually heard the voice of a small

child ask (presumably a parent) in Sinhala, whether the beating was for

real? The action was theatricalised so compellingly that it was almost

powerful to make a child wonder if there was actual physical harm being

done.

For instance, domestic violence may touch a disturbing chord in small

children. The ineptness of some viewers to grasp the nuanced gesture of

impending violence, which was taken for a ‘laughing matter’ of a comedic

nature, would create the wrong impression in children who are of course

there with elders and taking in the experience of watching a drama as

something of a ‘collective experience’.

What connections between the action on stage and the corresponding

audience reactions that occur may lend to how children make meaning of

their experience.

And another feature of the drama, which renders this production as

unfit for children is the coarsely foul language spoken in some parts of

dialogue.

My sole aim is to offer some food for thought as to the likely

susceptibilities of juvenile audiences when a story that contains

sensitive elements are shown on stage.

Daasa Mallige Bungalawa is a powerful piece of theatre. The impactful

performance that came alive on the boards on July 23 at the Lionel Wendt

Theatre must be applauded for the strength of talent shown by a cast

composed mainly of relatively lesser known faces in the domain of drama

and theatre.

A drama such as this will evoke in the average theatregoer a

conscientious afterthought by consciously grasping the deeper

significances of what are finely nuanced to reach deep into our

collective conscience as people. |