Animals and culture - a Lankan perspective

By Jayantha Jayewardene

Culture is defined by some as the totality of socially transmitted

behaviour patterns, arts, beliefs, institutions, and all other products

of human work and thought. These patterns, traits, and products are

considered the expression of a particular period, class, community, or

population. (For example, the cultures of India or Sri Lanka).

Animal welfare refers to the action that ensures the well-being

mainly of domestic animals. Animal welfare was a concern of some ancient

civilisations but began to take a larger place in Western public policy

in 19th-century, as in Britain. Today it is a significant focus of

interest in science, ethics, and animal welfare organisations.

|

Chained feet |

According to the definition of culture, given above, many animals

possess cultures too; they are 'socially transmitted behaviour

patterns'. For example, migratory birds, carnivores that hunt

cooperatively and tool-using chimpanzees. Most 'cultural' associations

with animals in the eastern world are based on religion. In the western

world the associations are more symbolic.

Former Kings of Sri Lanka established some of the world's first wild

life sanctuaries. Five of the kings governed the country under the

Maghata rule, which banned completely the killing of any animal in the

kingdom. The five kings were 1) Amanda Gamini (79 - 80 AD), 2) Voharika

Tissa (269 - 291 AD) 3) Silakala (524 - 537 AD) 4) Agga Bodhi IV (658 -

674 AD) 5) Kassapa III (717 - 724 AD).

The standards of 'good' animal welfare vary considerably between

countries, tribes and even contexts. These standards are constantly

reviewed and are debated, created and revised by animal welfare groups,

legislators and academics all over the world.

Animal welfare science uses measures such as longevity, disease,

behaviour, physiology and reproduction. The mitigation of distress is

also a key component. There is however, constant debate about which of

these indicators provide the best information.

Concern for animal welfare is often based on the belief that

non-human animals are able to perceive or feel things and that

consideration should be given to their well-being or suffering,

especially when they are under the care of humans. These concerns can

include how animals are slaughtered for food, how they are used in

scientific research, how they are treated in captivity or in

domestication (as pets, in zoos, farms and circuses), and how human

activities affect the welfare and survival of wild species.

Sri Lanka is a predominantly Buddhist country with around 70 percent

of its population nominally subscribing to a Buddhist worldview. The

Buddha in his teachings has said, "One must not deliberately kill any

living creature either by committing the act oneself, instructing others

to kill, or approving of or participating in acts of killing. Completely

abstain from the act of killing directly and indirectly, eat only pure

vegetarian food".

In ancient times the State protected animals, birds, and other living

creatures of the land pursuant to a moving plea made by Arahath Mahinda

who brought the message of Buddhism to Sri Lanka from India. This plea

was made to King Devanampiyatissa during their very first encounter at

Mihintale about 2,300 years ago.

The plea was "Oh! Great King, the birds of the air and the beasts

have an equal right to live and move about in any part of this land as

thou. The land belongs to the peoples and all other beings and thou art

only the guardian of it." Based on these words, King Devanampiyatissa

established what is believed to be the world's first wildlife sanctuary.

As a result this is now a part of the traditional culture of Sri

Lankans who have always had an ethical (if not carefully rationalised)

concern for the welfare of animals and who revere all forms of life.

However, while a reverence for life is deeply entrenched in society,

this does not always translate to a reverence for welfare, which is

frequently rationalised as the karmic fate of the animal.

The paradox exists, therefore, that while most people will not kill

animals, they would not go out of their way to improve the wellbeing of

an animal, either. Examples include temple elephants being kept in

chains for much of the time or made to walk long distances on burning

hot paved roads; stray dogs being allowed to 'live' on roads and public

areas with little or no care. The state, which is constitutionally bound

to protect and foster the Buddha sasana, itself undertakes activities

that are arguably inimical to the welfare of animals, e.g., through a

fisheries corporation, a leather products corporation, a silk

corporation etc.

Veterinary ethics

Mahatma Gandhi has said "The greatness of a nation and its moral

progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated". Historical

rock inscriptions and ancient chronicles e.g. Mahawamsa, reveal that

state protection was granted to animals and the slaughter of cows was

strictly prohibited. However cattle bones feature prominently in

archaeological digs all over the country, including Anuradhapura.

Today veterinarians are required to be more than good at their

clinical work. They must have a sound understanding of their moral,

ethical and legal obligations to the public, their peers and the animals

that they treat.

Animal laws are now growing as a legal discipline. This has enormous

implications for the veterinary profession. With increasing public and

legal attention on issues of animal welfare, it is vitally important

that veterinarians have a clear understanding of their manifold duties.

The non-fulfillment of these duties places the veterinary profession

and its members at considerable risk, including public criticism and

legal liability.

We need to remove the culture of impunity and non-accountability in

respect to abuse of animals. Veterinarians should be called upon, as

part of good practical ethics, to report suspected abuse of animals as

much as the public should.

Sri Lanka's Animal Welfare Bill is now before the Cabinet of

Ministers before it becomes law. Many Asian countries will soon follow

with their legislation.

"Good laws should not be confined to the statute book or be allowed

to remain as a dead letter but should be enforced with the same spirit

with which it was enacted". However, the Bill should contain laws that

are enforceable.

Current Legislation

The following list is a catalogue of legislation that has a bearing

on Animals and Animal Welfare:

• The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Ordinance, No.13 of 1907

• Animals Act, No.29 of 1958

• Fauna & Flora Protection Ordinance, No.2 of 1937 (Amended in 1997)

• Butchers Ordinance, No. 9 of 1893

• Animals Diseases Act, No.59 of 1992

• Municipal Council Ordinance, No.29 of 1947

• Urban Councils Ord. No.61 of 1939

• Pradeshiya Sabhas Act, No.15 of 1987

• Rabies Ordinance, No.7 of 1893

• Registration of Dogs Ordinance, No.25 of 1901

• Diseases of Animals Ordinance, No.25 of 1909

• Dangerous Animals Ordinance, No.38 of 1921

• Elephant Kraals Ordinance, No.1 of 1912

• Dried Meat Ord. No. 19 of 1908

• National Zoological Gardens Act, No.41 of 1982

Penal Code, No.2 of 1883

Elephants

In Sri Lanka, no other animal has been associated for so long with

the people in their traditional and religious activities as the

elephant.

This important cultural exploitation dates back to the pre-historic

era, more than 5,000 years ago. Elephants were often used in warfare,

with little concern for their wellbeing. It is not as if elephants

became associated with Buddhist culture because of some special

relationship: they just happened to be large, conveniently tameable

animals. No religious procession was complete without its retinue of

elephants, and many large Buddhist temples in Sri Lanka had their own

elephants as do private owners.

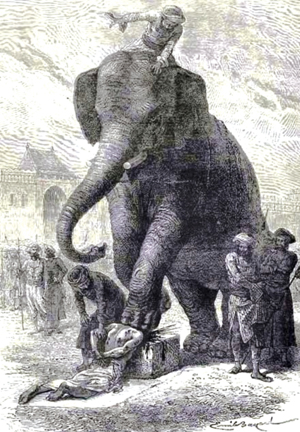

|

Crushing by elephant |

Ancient Sinhalese kings captured and tamed elephants, which used to

abound in the country, for various purposes. Elephants, suitably

caparisoned, have and still take part in ceremonial, cultural and

religious pageants and processions. Elephants have been used by man in

his wars in Europe and Asia. They have assisted him in his logging

operations and construction works.

They have also featured in various sports and combat during the

celebrations of the Sinhala community in Sri Lanka. They have helped in

timber operations and agricultural activities. In India they have

provided transportation for sportsmen indulging in shikars.

Historical records show that some ancient Sinhala Kings used

elephants to punish wrongdoers. One method was to get the elephant to

crush and dismember the victim

It is said that during the time of the Sinhala kings the elephant was

afforded 'complete protection' by royal decree.

This really only meant that their exploitation could be sanctioned

only by the king. This is not the same as what we mean by 'protection'

nowadays. The penalty for killing an elephant was death. With the advent

of the British to Sri Lanka this protection was withdrawn. On the

contrary large numbers of elephants were killed by the British under the

guise of sport.

Not only did the British government encourage and condone killing

elephants as a sport but it also paid a bounty for each elephant killed,

deeming the elephant an agricultural pest. Elephants were a common

element in Sinhalese heraldry for over two thousand years and remained

so through British colonial rule.

The coat of arms and the flag of the Ceylon Government from 1875 to

1948 included an elephant and even today many institutions use the Sri

Lankan elephant in their coat of arms and insignia - the Police

Department, Department of Wildlife Conservation, National Rugby Football

Union, Ceylon Government Railway etc.

[email protected]

(The writer is Managing Trustee, Biodiversity & Elephant Conservation

Trust

Sri Lanka)

To be continued

|