|

DRAMA

REVIEW

Jayalath Manorathana's Handa Nihanda:

Home truths and stark revelations

by Dilshan Boange

Thunder and lightning vied for prominence at the Wendt as Handa

Nihanda (Vocal and Silent), the latest creation of Jayalath Manorathna,

veteran of the stage and screen, came to life on March 4. A solitary

figure bearing a dim kerosene lamp appeared in a partially lit stage,

revealing the living room of an old household, and moving like a relic

in a forgotten world.

Residing at the very heart of the play are some revelations and

burning questions, the present cannot negate.

The

story revolves around the career, principles, and predicament of music

maestro Jamis Silva and his fellow musicians, who generally share the

sentiment of being bound to the ideal of preserving the integrity and

purity of song and music as an art, reflecting the ethos of a national

culture. Handa Nihanda is by no means a chauvinistic work of parochial

'localism'. It is a well balanced wholesome story that offers fact and

perspective on scales that must be grasped for the 'sound reason' it

offers. The

story revolves around the career, principles, and predicament of music

maestro Jamis Silva and his fellow musicians, who generally share the

sentiment of being bound to the ideal of preserving the integrity and

purity of song and music as an art, reflecting the ethos of a national

culture. Handa Nihanda is by no means a chauvinistic work of parochial

'localism'. It is a well balanced wholesome story that offers fact and

perspective on scales that must be grasped for the 'sound reason' it

offers.

This is a story today's Sri Lanka needs to hear and see.

In terms of stage craft, the set design was semi-realist and costumes

were of a realist motif fitting context and situation. The narrative

style blended the material world with musical elements that call for

stylisation of behaviour, which though theatricalised and not fully

realist at times, gave space for a facet of the surreal.

Music is a highly potent force through which a nation may project its

culture. But as culture itself is not static, music too will have its

dynamism to reflect change. What 'direction' however, should that

'change' take is one of the questions the play poses.

Is re-engineering classics with 'modern twists' necessarily

innovation? Let's not forget the issue is not just limited to song and

music anymore, as there is now a genre of fiction dubbed 'Mash-up

novels' to which belong Jane Austen classics 'reworked' as comic-horror

stories titled 'Pride and Prejudice and Zombies', 'Sense and Sensibility

and Seamonsters', whose 'authorships' are accredited to both Jane Austen

and the contemporary writers whose 'textual surgery' has reengineered

the Georgian era classics.

Initial ideation

The play does propound whether any authenticity or authorship can

actually be claimed over 'expressions' that lack originality in initial

ideation? Manorathna's creation, on the one hand instigates one to

ponder the merits of Sri Lanka's music revolution of the late 90s, which

is generally perceived to be accredited to the duo Bhathiya and Santhush

and those who followed in their footsteps. On the other hand, the play

presents the younger generations' need to break free from the

limitations imposed by elders and their ethos.

I couldn't help but feel how stimulating this play is as a work to

spur the people's need to engage in active discourse over what creates

the clash of generations in the arts and how the need for preservation

comes to blows with the need to change. And let's not forget Handa

Nihanda mounts the stage in the aftermath of the public debate and

furore sparked over songstress Kishani Jayasinghe's operatic rendition

of Dhaanno Budunge on Independence Day this year.

In Handa Nihanda, voices of the young generation speak vociferously,

about how music is evolutionary and explicate the music that was birthed

out of oppression in the West. Blues and jazz speak through rhythms of

jaggedness and sporadic fusions as the sound of frustrations and

indignations of their creators. But how authentically does Sri Lanka's

new generation grasp and realise this as practitioners and experimenters

of those music genres without subscribing to mimicry and fusion of

traditions for the sake of being sophisticated? And can they claim

creativity in originality of ideation for a work? This is somewhat a

hard hitting argument brought out in Manorathna's play.

Along the critical discourse the play builds, some of the

investigations offered is the question as to how genuine and reliable

the leftist party, the 'Sama Samaja Pakshaya' led by N.M. Perera is.

Jamis Perera and his fellow artistes are patriots who believe in

independence from the British. Interestingly, this play offers insights

on how the segment of people represented by the protagonists viewed with

great ardour the independence struggle of India and their nationalist

sentiment, which occupies a notable place in their argumentative

discussions as artists of intellect. The clash of opinions between

Tagore and Ghandi cited, in my opinion, indicate how within the Indian

national(ist) movement, the belief in art as an individual freedom may

have been incongruent with politics for freedom.

Through the machinations of the character Nicholas Epa, the

unapologetic trader in music as a commodity, the plays depicts the

artiste as the prisoner of the businessman, faced with the ultimatum of

either selling out to big money or being wiped out by penury.

Is there a price on conscience? Is a conscience worth fighting for?

This is a question Manorathna's play grapples with. 'What purpose

does/should art serve?' is not a question ever answered to finality in

society. Does or should, music as an art exist for its own sake as an

aesthetic creation to be enjoyed apolitically? However that may be,

Silva's adamant refusal to create art for the glorification of the

British monarch speaks soundly of how he views his art in relation to

not serving politics he cannot hold true to his conscience. Is there a price on conscience? Is a conscience worth fighting for?

This is a question Manorathna's play grapples with. 'What purpose

does/should art serve?' is not a question ever answered to finality in

society. Does or should, music as an art exist for its own sake as an

aesthetic creation to be enjoyed apolitically? However that may be,

Silva's adamant refusal to create art for the glorification of the

British monarch speaks soundly of how he views his art in relation to

not serving politics he cannot hold true to his conscience.

Brutal reality

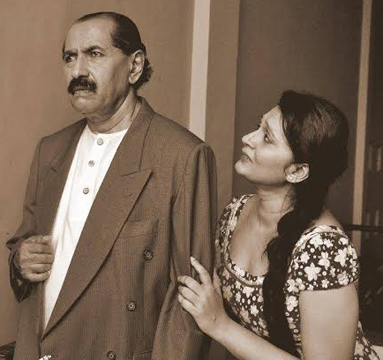

Early on in the play, Silva played by Manorathna says "the artiste

suffers in order to give pleasure to the enjoyers of art'. I am reminded

of a line in the English version of Valmiki's Ramayana that I read as a

teenager -From shoka (sorrow) comes shloka (verse). Epa, played by W.

Jayasiri, presents brutal reality as an unapologetic creature of the

consumerist system, mocking the aged musicians for not planning for

their twilight year in their career's heyday, and who with their ailing

health are in dire straits towards the end of the play. Epa pronounces a

bitter truth, that "the time to think about 'dusk' is at the break of

dawn itself".

Among

the failings of the celebrated maestro Silva, is his family life. His

daughter flatly tells him that although his knowledge of eastern music

is optimum, his understanding of the eastern woman is nil. For whom does

the artiste pine? Silva himself, even in his debility, refuses to sell

out and says it is the hopeful thought of composing another song yet

again that kept him going, even after losing his parental home to a

mortgage and being forced to live an impoverished life in a rented

house.

The final segment of the story really delivers an uppercut to the

contemporary trends of TV station driven 'reality

star' ventures and what they offer in terms of both 'artistes and

performances' and 'judges and adjudication'. The 'Grand Pa Finale' TV

Show that features the aged musicians, and makes of them publically

designated charity cases, depicts how the older generation and their

dignity are being buried by today's 'politics of marketing'. The end is

tragic, and to the sensitive viewer, benumbing. As in the start thunder

rumbles gently, and darkness descends, to mark the end.

What Manorathna has offered is a contemporary critique of our

climates that revives times past to reflect on and reassess the moral

worth of paths charted for us by the politics of market-economy

consumerism. Handa Nihanda is a work to be saluted and celebrated. |