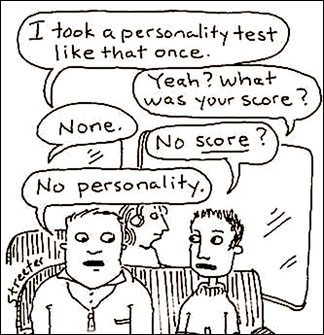

How do you measure personality?

by Judy Skatssoon

Knowing yourself is tricky, and so is personality science.

Are you stable or thin-skinned? Anal-expulsive or anal-retentive? Are

you Type A or Type B? An ISTJ or an ENFP? Piglet, Tigger, Eeyore or

Pooh? The recent boom in personality testing has created a mindboggling

variety of options for discovering your personality 'type'. Are you stable or thin-skinned? Anal-expulsive or anal-retentive? Are

you Type A or Type B? An ISTJ or an ENFP? Piglet, Tigger, Eeyore or

Pooh? The recent boom in personality testing has created a mindboggling

variety of options for discovering your personality 'type'.

Personality tests are used for job interviews, career guidance,

sports psychology and marriage counselling, as well as for therapeutic

and forensic purposes.

But what can they really tell us about ourselves? Personality through

history We've been trying to pin personality down since the days of the

ancient Greeks, when Hippocrates came up with the idea that four body

fluids, or humours (yellow bile, phlegm, blood and black bile), governed

our health. Based on this theory, the Greek physician Galen suggested in

200 AD that the humours influenced not only health, but our

personalities.

People with an excess of yellow bile were therefore choleric (hot

tempered), those with too much phlegm were phlegmatic (calm and

unemotional), an excess of blood resulted in a sanguine personality

(optimistic and cheerful) and black bile was associated with melancholic

types (gloomy and depressed).

Sigmund Freud, working in the late 1800s and early 1900s, looked not

to our bodily fluids but our unconscious.

He linked critical stages of development like weaning, toilet

training and sexual awakening to personality, giving us a legacy of

orifice-related personalities such as 'anal' and 'oral' types.

The anal-retentive, for example, is compulsively ordered, tidy and

perfectionist; this, so the theory goes, is a result of too much

punishment during toilet training.

The testing boom

Current theories tend to categorise personality under a combination

of traits, such as introversion or extroversion, and have spawned an

entire industry based around testing (see box below).

To qualify as a factor that is useful in testing, a trait must differ

between individuals, and it must be relatively stable over time and in

different contexts.

Dr Miles Bore is a registered psychologist and lecturer at the

University of Newcastle who specialises in pyschometrics, or

psychological measurement, and personality assessment.

He says personality testing is driven as much by fashion as by any

inherent usefulness, although tests can be helpful in some areas, such

as choosing a career path. "There's been a lot of criticism of

personality tests and their accuracy and it waxes and wanes in the

literature," he says.

Bore says while no test is a perfect predictor of personality, they

can be a rough guide of how individuals will act in certain situations.

"If you sit a personality test, can it tell you or somebody else

exactly what you're going to do in every situation in the future? Well

the answer is clearly no," he says.

"But they can indicate the likelihood of certain behaviour in typical

situations."

A review of the big five traits in the 1999 Handbook of Personality

found that research in adolescents showed those with high

conscientiousness and openness performed better in school.

Among adults, conscientiousness was the only personality factor to

predict overall success at work, but people who scored higher on

agreeableness and neuroticism were the best performers in jobs requiring

group work, and those who scored high on extroversion did well in sales

and management.

Psychoanalyst Stephen Carroll is a skeptic. He believes personality

tests reflect the 'corporatisation of psychology' and don't prove

anything other than that a person can tick a box.

"It's bad science, it's hocus pocus, it goes to the realms of

superstition," he says. "There are people who put too much faith in

tests, who say 'I think you're a KZ9' and it's 'my god how did you

know?'

It's like saying 'you're a Capricorn'." Bond University's Professor

Greg Boyle, senior editor of the four-volume Psychology of Individual

Differences, says it's wrong to talk about personality "types" É" rather

than scores along a scale É" because personality consists of "continuous

dimensions".

"To call a person an introvert or an extrovert, really we're only

talking about a small percentage of people who are right at the extreme

ends of the distribution," he says.

"The vast majority of people fall somewhere in the middle." Common

personality tests Revised NEO-PI test. Developed by Paul Costa and

Robert McCrae, the revised NEO-PI test measures the so-called 'big five'

traits: neuroticism, extroversion, openness to experience, agreeableness

and conscientiousness. It is based on the five-factor model, the

dominant model of personality since the mid-1980s.

16PF test. First published in 1949 by Raymond Cattell, the 16

Personality Factor questionnaire assesses 16 traits including warmth,

dominance, privateness and perfectionism.

Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI). Designed in 1958 by Isabel Briggs

Myers and Katharine Cook Briggs, the MBTI is based on Jungian theory.

It describes people by a combination of letters based on four

dichotomies: extroversion or introversion (E or I), sensing or intuition

(S or N), thinking or feeling (T or F), and judging or perceiving (J or

P). This results in 16 different types, or four-letter code

combinations, such as an ENFP or an ISTJ.Novelty tests.

The Hundred Acre Wood personality test tells you whether you're most

like Tigger, Pooh, Piglet or Eeyore. Other novelty tests compare you to

the characters in Harry Potter, or a breed of dog.

Can you change your personality?

Professor Greg Boyle believes basic personality traits are primarily

a result of the anatomy, structure and functioning of individual brains,

although experience and learning can modify personality.

"People's brains operate differently and some people are more

extroverted depending upon the level of arousal or activation of the

brain," he says.

But this doesn't mean our personalities are fixed.

"Although personality traits are often said to be permanent fixtures

in the profile of an individual -they are not necessarily the fixed,

immutable dispositions that some people have thought.

"Personality differences show up in the brain, but brains, like

personality traits themselves, are susceptible to learning. As our

personality changes, so will the brain." Dr Doris McIlwain, a

personality psychologist at Macquarie University, says genetic studies

comparing non-identical twins living in the same environment with

identical twins living in the same environment have shown that some

aspects of our personality, like the extrovert/introvert factor, are 60

per cent due to environment.

More recently, a study by researchers from the University of Michigan

looked at the closely related (and therefore genetically similar)

population of the Mediterranean island of Sardinia.

That study, published in the journal PLoS Genetics, concluded that

genes account for only 19 per cent of documented traits like

agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism and extroversion.

"My personal view is that we have evolved to have very diverse

personalities and thatÉ?›personality may be much less deterministic than

other human characteristics," says Associate Professor GonA�alo Abecasis,

one of the authors.

Professor Greg Boyle says research has shown it's possible to develop

or at least change "the outward expression" of your personality.

In a study of students, published in the journal Psychological Review

in 2002, he found personality traits such as ego strength and dominance,

as measured in the Sixteen Personality Factor questionnaire (16PF), were

susceptible to learning.

Several recently published studies confirm a more fluid view of

personality, says Boyle. A 2006 review found that social dominance,

conscientiousness and emotional stability, for example, tended to

increase between 20 and 40 years of age.

Even in middle and old age, there was significant change in four out

of six personality traits, the reviewers found.

"Given that people have a very highly developed cognitive ability;

it's therefore possible for humans to consciously try to modify their

behaviour and interpersonal relations," says Boyle. |