|

[email protected]

Psychological difficulties in children

by Dr. R. A. R. Perera

Most children show isolated psychological symptoms at one time or

another and, to a considerable extent, these are a normal part of

growing up.

However, some children suffer from psychiatric disorders that

interfere with normal development. Accordingly, one of the first tasks

when a child is referred to the clinic is to assess whether the child

has a disorder.

In this context, a psychiatric disorder can be defined as behavioral

or emotional symptoms that are so prolonged or so severe as to cause

suffering to the child or to others, social restriction or impairment of

normal development.

Some symptoms, such as fire-setting or deliberate self-harm, are so

extreme that they need only occurs once to be regarded as abnormal.

Most symptoms are only abnormal, however, if they persist and if they

are seen in several situations, and should be regarded as a disorder

only if they lead to impairment.

Diagnosis / Assessment

1. Age and sex appropriateness

2. Socio - cultural settings

3. Duration/Pervasiveness

4. Type of symptom/impairment a. Suffering to the child, b. Headicap

to the parents, c. Social impairment, d. Interference with development.

Emotional disorders

Most emotional disorders of childhood are exaggerations of normal

development trends. The onset is usually during the developmentally

appropriate age period. For example, it is normal for infants to show a

degree of anxiety over separation from people they are attached.

When this anxiety becomes severe, or persists in to later childhood

or adolescence, it is termed separation anxiety disorder. Similarly,

when stranger anxiety persists beyond the preschool years, the diagnosis

of social anxiety disorder is justified. In adolescence, specific

fearfulness, though less common, usually takes the form of school

refusal or adult type neurotic disorders, such as social phobia or

agoraphobia.

Anxiety disorders are among the commonest psychiatric problems in

childhood and occurring in about 3% of 10 year olds. Genetic factors are

important. The parents are often anxious and communicate their anxiety

by behaviours such as over-protectiveness. Some cases of anxiety,

particularly specific fears, are precipitated by stress.

Management: consists of the reduction of stress, behavioral therapy

for specific symptoms (e.g. graded exposure to the fearful situation)

and general treatment such as relaxation. Anxiolytics may be helpful for

severe cases, but should not be prescribed for long periods.

Affective disorders

Depressive disorders occur in prepubertal children, but are uncommon

(1%). (In adolescence 4% - girls, 2% - boys). The main clinical features

are similar to adults. But somatic complains and anxieties are more

common in prepubertals than in adolescence. Mania is uncommon.

Infants who have been severely deprived or abused sometimes show a

state of withdrawal and retarded development (anaclitic depression).

Children and adolescence with depressive disorders tend to have parents

who are depressed, but these links are probably more a reflection of

environmental (e.g. poor parenting) than genetic factors. Depression in

young people is commonly precipitated by adversity.

Management: consists of reducing this adversity, and the use of

individual psychological interventions (e.g. cognitive behavioral

therapy, which can be administered to children over 10 years) and family

therapy. Antidepressants should be used cautiously for adolescence due

to the risk of overdose. Most recover within few months but relapse can

occur.

Many children attending medical services have unexplained physical

symptoms (e.g. abdominal pain and headache) these children tend to come

from families that have health problems and high academic expectations.

In many cases, the child is in some kind of predicament in which

other avenues have been blocked; for example, the child may feel unable

to achieve what the family expects academically. Pre-existing physical

problems in the child or in a relative may determine the kind of

symptomalgy shown.

Management: Involve the psychiatrist/psychologist and the

paediatrician closely, changing the family focus from physical to

psychological issues, and placing emphasis on leading as normal life as

possible (e.g. returning to school).

Conduct disorders

Conduct disorders are characterised by repetitive antisocial

behaviour that lasts for at least for 6 months. In young children, the

clinical picture is dominated by markedly opposition behaviour (e.g.

defiance, hostility, and disruptiveness) that is clearly outside the

normal range. In older groups' behaviours such as stealing, truancy,

fighting, lying and running away is seen.

In severe cases, fire setting, or cruelty to animals and other

children are seen. Conduct disorders are usually associated with poor

peer relationships. Conduct disorders occur more in towns (10% than in

rural areas. More in boys than girls.

There is a strong link with discordant interfamilial relationships

and abused parents are often inconsistent in applying rules and may be

critical and rejecting the child. About 30% have reading difficulties

and few have organic brain disease.

Management: Depend on the presenting problem and the commitment of

the parents. Behaviourial methods are effective for young children.

Medication is of little value. Older children with severe problems have

to be in special schools. Children with few symptoms and good peer

relationship do better. Children with early onset and poor peer

relationship have 30% risk of personality disorders in adulthood.

Almost all adults with anti-social personality disorder have had

conduct disorder as children.

Hyperkinetic disorders

Hyperkinetic behaviours are overactive behaviours and inattention.

Diagnosis depends on these two problems in more than one situation (e.g.

home, clinic, classroom), and long-term persistence of the behaviour.

The diagnosis is difficult in less than 5 years due wide normal

variations. Several other abnormalities are associated with the

disorder, including impulsiveness, conduct disorders and learning

difficulties. Prevalence depends on diagnosis criterias.

Brain dysfunction resulting from genetic processes or early brain

damage is important in the etiology. Hyperkinesis may occasionally be

the result of early social deprivation.

Side effects to drugs or additives are also important. Management:

Counsel the parents of the biological factors. Changing the environment,

for example by moving to a house with a garden, is helpful, but

difficult to achieve. Behaviourial programs may be helpful. Stimulant

medications (methyl phendiate) may be helpful in severe cases.

Hyperkinetic disorders are associated with an increase risk of conduct

disorders in adolescence.

By 5 years of age 10% of children will still wet at night and 3% will

wet during the day. Enuresis (inappropriate emptying of the bladder in

the absence of organic disease) in a child over 5 years may be nocturnal

diurnal or both.

The most common cause is an inherited delay in maturation of the

nervous pathways that control micturition. But there is increased level

of behaviourial problems in these children especially in girls.

Management: Children should be reassured that they are not the only

ones to suffer from the problem. Parents should be advised not to punish

the child. But rather to encourage the appropriate toilet habit. This

process, known as shaping should be charted and rewarded on 'dry' days.

It may be necessary to treat associated psychiatric disorders.

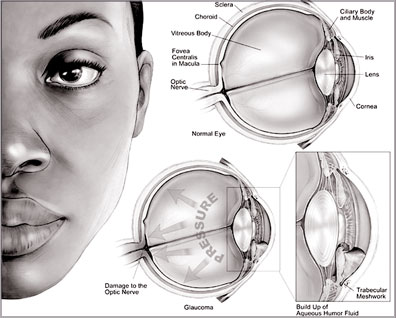

Glaucoma

Early diagnosis and treatment could prevent further deterioration: Early diagnosis and treatment could prevent further deterioration:

Glaucoma occurs when the nerve at the back of the eye becomes

damaged. This can cause a person's sight to deteriorate and can lead to

blindness.

What is glaucoma? Glaucoma is the name given to a group of conditions

that affect the eye.

There are four different types of glaucoma - acute, chronic,

developmental and secondary. In each case, the optic nerve behind the

eye is damaged. This nerve carries information from the eye to the brain

enabling us to see. This damage can be caused by a weak nerve or more

usually by the build-up of fluid in the eye. This occurs when fluid in

the eye cannot drain properly.

Acute glaucoma can occur suddenly and can be painful. If left

untreated, it can lead to blindness. untreated, it can lead to blindness.

Chronic glaucoma is the most common form of the condition. The

drainage channels from the eye become blocked over time and vision

gradually becomes impaired. Developmental glaucoma mostly affects babies

and young children. It is rare but potentially serious and is caused by

malformation of the eye.

Secondary glaucoma occurs when another problem in the eye causes

fluid to build-up and eyesight to deteriorate.

How common is it?

By the age of 40, about one person in every 100 has some form of

glaucoma. However, the incidence rises steadily as people get older. By

the age of 70, about one person in every 10 has some form of glaucoma.

People who are of African origin are more likely to develop the

condition. People who are highly short-sighted, those with diabetes and

those with a family history are also at increased risk.

In the UK people over the age of 40 and with a family history of

glaucoma are entitled to free eye tests on the NHS every two years.

What are the symptoms?

Acute glaucoma can be painful. The sudden increase in pressure can

make the eye red.

Eyesight can deteriorate and may even blackout. There may be nausea

and vomiting. Chronic glaucoma is less easily spotted. There is no pain

and the deterioration in eyesight may be subtle.

Some people go for an eye test after noticing their sight is less

good in one eye than the other. The fact that this type of glaucoma can

creep up on people is one reason why doctors advise regular eye tests.

How is it treated?

Glaucoma is treated by reducing pressure on the eyes.

Eye drops are a common first approach. However, if they fail to

unblock the drainage channels then an operation may be needed.

These can take the form of laser surgery or a trabeculectomy - an

operation to improve drainage of the eyes.

Can it be cured?

In many cases, the damage that has been caused by the glaucoma cannot

be reversed. However, early diagnosis and treatment can prevent further

deterioration

BBC.com

Football is 'good for men's mental health'

by Helen Neill

Playing in a football team can help men feel more confident and

enthusiastic about their lives, according to researchers. Playing in a football team can help men feel more confident and

enthusiastic about their lives, according to researchers.

A new study, carried out by the University of Nottingham, suggests

the sport can improve the mental health of men who are suffering from

problems such as depression.

They evaluated more than 100 men playing for league teams in the

north west of England.

Bonding experience

Lead researcher Alan Pringle said that one of the benefits of playing

football regularly is the friendships men have with their team-mates.

He told Newsbeat that depression can make people become lethargic and

withdrawn and that "people who wouldn't normally go out, will play

football".

He said it acts as "therapy in disguise", and that many men talk

about the confidence they get from working with their own team, and

facing the opposition.

Nine out of 10 felt that their mental health had improved

significantly since they joined a team, and more than 70% said that they

were now more optimistic about the future.

Doctors are already encouraged to "prescribe" exercise to people who

are suffering from mild depression.

Mind spokesperson Alison Kerry said: "If you're feeling low, outdoor

exercise is a fantastic way of boosting your mental wellbeing.

"Men often find it harder to talk about their problems than women and

football presents an opportunity for greater social interaction in an

informal and fun way." |