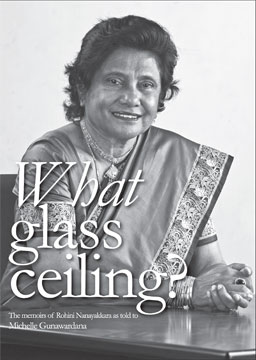

Top banker scales the upper echelons

What glass ceiling?

Author: Michelle Gunawardane

Reviewed by Prof. Yasmine Gooneratne

An invisible upper limit in corporations and other organisations,

above which it is difficult or impossible for women to rise in the

ranks. Discrimination exists in many forms.

When Michelle Gunawardane asked Rohini Nanayakkara, former

Chairperson of the Bank of Ceylon, whether the 'story' she was about to

relate to her would be about 'breaking the glass ceiling' in the area of

corporate management, it was evident that it was 'negative'

discrimination that Michelle had in mind: that unacknowledged

discriminatory barrier which prevents women and minorities from rising

to positions of power or responsibility within an organisation.

'Positive' discrimination is something else altogether, and while

there is nothing in the least amusing about negative discrimination

(particularly to its unfortunate victim), positive discrimination has an

amusing - if slightly cynical! - side. 'Positive' discrimination is something else altogether, and while

there is nothing in the least amusing about negative discrimination

(particularly to its unfortunate victim), positive discrimination has an

amusing - if slightly cynical! - side.

I found myself once on the selection board of an Australian

university which was debating the appointment of a Professor of Physics.

Science has never been my strong suit, and I mentioned (privately, to my

neighbour) that I'd really like to know why I'd been invited to serve on

this particular Board."It's one of our regulations," he told me, "that

at least one member of a Selection Board should be from a department or

faculty quite unconnected with the discipline that is under discussion.

You are that member."

Non-scientist

Well, this sounded fair enough - until I looked around me and

observed that I was not only the single non-scientist on the selection

board, I was also the only person present who was neither male nor

Australian-born. 'Positive discrimination', which had been officially

set up to counter racial and gender discrimination in the work-place,

had managed to merge four different personae (and four different votes!)

into one.

It is most unlikely that Rohini Nanayakkara would have ever

encountered racial discrimination in the course of her meteoric rise to

the top of the banking 'tree': We graduated in the same year (1959) from

the University of Ceylon at Peradeniya, and although we did so from

different departments, I am positive that she and I have that happy

experience in common, of our work in both classroom and examination hall

being assessed entirely on its merits and not according to 'quotas'

based on race or community as happens in some other countries in our

region.

As for gender discrimination - well, some old-fashioned academics in

Sri Lanka did believe in the 1950s that women's proper place was in

their homes, bringing up children, and not in university staff rooms.

I met one such in Australia, a very senior Professor of Mathematics

who did not like women, and did not believe any woman capable of

understanding or teaching his subject. Hopeful young female candidates

for mathematics were discouraged by him, personally, on the telephone.

At scholarship meetings that he chaired, which another woman Professor

(of History) and I attended on behalf of our students, Professor A.

would begin proceedings by looking genially around the table of male

academics, and saying:"Good morning, gentlemen! Shall we begin?"

Confrontation

A little of that sort of thing goes a long way. Since it was obvious

that confrontation would be useless in his case and that, due to his

attitude, our students were likely to suffer, I suggested to the Head of

the English Department that he should discreetly take my place on the

committee, and tackle Professor A. himself. Which he did, with excellent

results for our students.

So, although Rohini Nanayakkara can look back today over her long and

successful career, and cheerfully say, "What glass ceiling?" we can be

certain that gender discrimination must certainly have come her way in

the banks at which she worked.

It was inevitable that it should, for banking (like engineering) was

for a very long time an area of employment that was considered

unsuitable for women here and elsewhere. The term "glass ceiling" as it

operates in corporate management was, I understand, first used by two

women at Hewlett-Packard in 1979, Katherine Lawrence and Marianne

Schreiber, to describe how while on the surface there seemed to be a

clear path of promotion, in actuality women seemed to hit a point beyond

which they seemed unable to progress. On becoming CEO and chairwoman of

the board of Hewlett-Packard, Carly Fiorina proclaimed that there was no

glass ceiling. (Not unlike Rohini Nanayakkara's reply to Michelle: What

glass ceiling?) And yet, after her term at Hewlett-Packard, Ms Fiorina

admitted that her earlier statement had been a "dumb thing to say".

Fascinating

The point at issue surely is, not so much whether glass ceilings

exist - for they do - but how they are to be circumvented.

The story that the book relates is a fascinating one. Here was a

young woman totally involved with her happy life within her family, who

wouldn't have gone to university if her elder brother hadn't paid her

fees. Apparently devoid of either ambition or a plan for the future, she

made friends at Peradeniya, enjoyed the university's social life,

graduated ....and then spent 'a lazy year' at home with her parents.

Pure chance made her spot an advertisement for which she applied and was

successful.

Following that almost accidental entry into the field in which she

was to make her career - banking - came a journey which, by its smooth

and seemingly unbroken progress to the top, takes the reader's breath

away.

How was this achieved? What can young women who wish to emulate her

example do to make that possible? Qualities of character emerge in the

course of Rohini's frank and simply told story, which answer some, if

not all, of these questions.

The first of these, notable from the very start, must surely have

been her openness, even as a schoolgirl, to new ideas and new

experiences. If, as the saying goes, 'Knowledge is power', the expertise

that she has demonstrated at every stage of her rise must have been

based on her willingness to listen and learn.

The second, emerging when she was an undergraduate at Hilda

Obeysekere Hall, would have been her ability to organise and order her

activities. Rohini would not have been the type of student who leaves an

essay or examination answer unfinished, and hopes for the best.

Bravery

A third, I should think, would have been courage. Accepting and

dealing with the challenges thrown up by corporate life after an

adolescence passed quietly at home, takes bravery of a very special

kind.

When she became aware that her chances of success in applying for a

particular appointment were under threat because she was a woman, Rohini

had the courage to inquire directly (but quietly) of the Chairman

whether gender considerations were likely to affect the outcome. What

could he say, but: "Of course not!"

A fourth characteristic that is quite impossible to miss as the

tentative, even diffident ex-student finds her feet in a world outside

family, school and university, is tenacity. And a fifth, which the other

four have helped to develop, must definitely be her ability to get on

with people.

Among the many colleagues who have helped her advance, Dr Nimal

Sanderatne and Nissanka Wijewardene are two seniors whom Rohini

acknowledges with gratitude as her mentors, providing her with the

assurance of fair play whenever she was threatened by discrimination.

And finally one might ask: What part did ambition play in this story

of success?

Many women are conditioned to believe that while ambition is a

perfectly acceptable attitude for men to cultivate, the desire to soar,

to excel, is dangerously unfeminine, and should therefore be off-limits

for women. Many mothers and aunts become restive and nervous when girls

develop interest in things other than dress and domesticity: and yet, as

many life-stories demonstrate, one thing is certain - nothing can be

achieved without ambition.

Rohini Nanayakkara in maturity is an elegant and very charming woman.

But all the personal charm in the world cannot, by itself, impress

seniors who know very well what they are about. It cannot convince

anxious colleagues that they are in the presence of comradeship and not

of cut-throat competition. Nor can it placate the unions, ever keen to

find some flaw in senior management that calls for revolution!

Beneath the gentle, quiet manner that is Rohini's outward 'signature'

is absolute reliability, an understanding of corporate affairs that is

known by everyone she works with to be soundly based in experience, and

a creative ambition to ensure that a client's interest is always kept in

view.

Here is a book that tells a story and teaches valuable lessons. My

congratulations to Michelle Gunawardane, who has told it with such

sensitivity, and to the publishers, who have given it such an attractive

presentation. |