Troubled waters in Bangladesh

by Tahmima Anam

In August 1947, the architects of an independent South Asia had

little idea that they were laying the groundwork for the creation of not

two, but three countries.

The two-nation theory of Mohammad Ali Jinnah turned out to be

harbinger of three nations - India, Pakistan, and eventually,

Bangladesh. And if India was built on secular lines, and Pakistan upon

religious unity, then Bangladesh was created by the linguistic and

cultural nationalism of the Bengali people.

The founding fathers of Bangladesh were also interested in another

idea, one that had yet to fully take root in Pakistan: democracy.

|

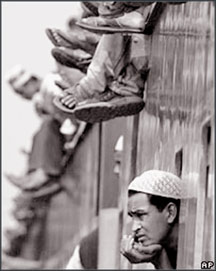

The opposition has protested against electoral corruption |

Between the 1947 partition of India and the creation of Bangladesh,

Pakistan had struggled to establish a democracy, as power passed from

one military ruler to another. On the eve of Bangladesh's birth, we

vowed to do better.

Since independence in 1971, Bangladesh has been at pains to create

democratic institutions that will weather the multiple challenges of

poverty, globalisation, climate change, corruption, and the handicap of

being a young country in a world of established military and economic

powers.

But far more than our neighbour India, the political leadership in

Bangladesh has had a troubled relationship with democracy. Again and

again the army has muscled into power.

The longest-standing example of this was the dictatorship of General

Hossain Mohammad Ershad, who ruled Bangladesh for nine years, destroying

our nascent democratic institutions and creating the foundations for the

unbridled corruption that has since hobbled the nation.

Through mass protests and a popular campaign of agitation, Ershad was

overthrown in 1991, and since then, three general elections have taken

place in Bangladesh.

For three consecutive elections, we have had a large and enthusiastic

electorate who have ushered in freely elected governments and

representative parliaments. Although young and sometimes faltering, we

have been understandably proud of our fledgling democracy.

|

Bangladesh faces an uncertain future |

But our democracy has been nothing if not deeply flawed. The last 15

years have seen each ruling party brutally repressing the opposition; in

retaliation, opposition parties have boycotted the parliament, sometimes

for years at a time. And worst of all, the accountability of our

politicians has lessened as corruption, greed, and blatant disregard for

their offices has increased without pause.

These trends laid the groundwork for the events of January 2007, when

the political landscape in Bangladesh underwent a dramatic shift.

Instead of looking forward to another chance to exercise our

democratic rights, we realised, on the eve of the fourth election, that

this election was planned and engineered to give victory to the ruling

party.

After a series of protests against electoral corruption led by the

opposition Awami League, a military-backed caretaker government stepped

in, promising to clean up the political landscape and hold free

elections.

Although the people at the helm of this shift wore military uniforms,

we applauded them, because without them we would have had a sham

election.

And when they started arresting corrupt politicians, officials and

businessmen who believed they were above the law, we still applauded

them, because those people who had been the source of institutional

decay were suddenly held accountable for their actions.

The military-backed caretaker government is heralding a series of

reforms - electoral, bureaucratic, and institutional.

|

The poor pay the price for instability |

They have also instigated reforms within the political parties, which

have begun a close examination of their party members. But the fact

remains that these reforms have not have taken place within a democratic

framework, and that raises serious questions about their long-term

sustainability.

Instead, we have a non-elected, military-backed regime performing

tasks without due process that should have been in the remit of our

political leadership.

The only way to ensure the survival of democracy in Bangladesh is if

the army does as it has promised: holds an election and returns to its

barracks.

Otherwise, even if the military cleans up the political landscape,

even if they arrest all the corrupt politicians, even if they seize the

illegal assets and raze the buildings that were made with black money,

who will become our new democratic leaders? Who will we be left to

believe in? Only those who wrested power in the first place: the army.

If they do not hand over power to elected leaders, they will emerge

as the most powerful force in Bangladeshi politics. And a victorious

army, as history has taught us time and again, is a dangerous thing. In

the meantime, as with any major political or institutional instability,

it is the poor who have to pay the price.

The monsoon floods that have hit Bangladesh are some of the worst in

recent years. Millions of villagers are marooned on the rooftops of

their homes, waiting for relief supplies, food, and clean water.

The government has made confident declarations about the food supply,

and of their own commitment to providing disaster relief.

But as everyone in Bangladesh knows, the state can only do so much in

reaching the far corners of the country. For this, they have relied

heavily on the grassroots outreach of the political parties.

With the current embargo on all political activity, the parties do

not have the liberty of reaching their constituents in rural Bangladesh.

Flood relief has not yet begun to stem the tide of hunger, disease, and

homelessness.

The floods, tragic as they are, remind us of the importance of

democratic politics in a country where the need for democracy among a

largely illiterate population has been questioned time and again.

We need a rich and well-functioning democracy, not to provide

credibility to a corrupt political system, but rather to ensure that the

state acts and exists for all its citizens, rich, poor, sheltered, or

homeless.

-Tahmima Anam was born in Dhaka, Bangladesh in 1975. She attended

Harvard University where she earned a PhD in Social Anthropology. She

lives in London. Her debut novel, A Golden Age, was published earlier

this year

BBC |