|

Two Personal Investigations of the Act of Reading:

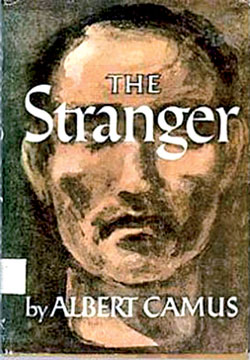

Understanding Camus

By Pablo D’ Stair

I first encountered Albert Camus’ L’etranger as a rather ugly,

pocketsized edition under the title The Stranger. It was the Stuart

Gilbert translation I read and I remember the first time I came across a

different translation, this by Matthew Ward, I was violently repelled by

it. The translation was incorrect—this was not The Stranger, not what

Camus had said to me when we first met and so the text felt to me an

imposter.

In particular was the final passage of the piece, the final sentence.

Gilbert has it as “For all to be accomplished, for me to feel less

lonely, all that remained to hope was that on the day of my execution

there should be a huge crowd of spectators and they should greet me with

howls of execration” and Ward has it like this “For everything to be

consummated, for me to feel less alone, I had only to wish that there be

a large crowd of spectators the day of my execution and that they greet

me with cries of hate.” In particular was the final passage of the piece, the final sentence.

Gilbert has it as “For all to be accomplished, for me to feel less

lonely, all that remained to hope was that on the day of my execution

there should be a huge crowd of spectators and they should greet me with

howls of execration” and Ward has it like this “For everything to be

consummated, for me to feel less alone, I had only to wish that there be

a large crowd of spectators the day of my execution and that they greet

me with cries of hate.”

Much differs, of course, even in this short span of words, but it was

the last four that so unsettled me.

***

“…with howls of execration”—I don’t know that I literally understand

what the words mean, if at this moment someone asked me to define

“execration” I’d be unable to. At the time of my first encounter with

Gilbert, though, I didn’t care, felt I understood the expression as a

totality. To me a “howl” was mournful pain, desolation, fear mixed with

anger and I assumed “execration” was a type or degree of such

despair—the word suggested a lost, almost soulless pitch to something,

an agony too painful to articulate.

Yes, despite my superficial lack of understanding, I bonded with this

phrase, it imprinted—this was the way the novel ended and moreover it

was imperative the novel end just so, every word preceding these four

was momentum to make them impact, severely, absolutely.

“…with cries of hate”—In comparison to Gilbert’s take, this seemed

watered down, polite, even timid—“cries of hate” were simpleton,

understandable, “hate” so ordinary, even unintelligent, precise but

blundering. And “cries” were not howls, were blubbering,

self-referenced, aimed and built of something specific and born of the

crier—cries were cried out with some purpose.

No, this novel, Meursault’s confronting the naked absurdity of man,

could not culminate like this, it simply could not.

***

Of course, I had to admit I was comparing Gilbert to Ward, nothing to

do with Camus. Then it struck me I ought to see what Camus had to say

about the matter—I think it was with an odd, cocky swagger I decided

this, decided I was going to prove myself “right.”

As an adolescent American, I admit the novel in its original language

struck me as an oddity, as though it was more appropriate it exists in

my easy, native tongue than that of its author—logic dictated against

this, though. Camus said what he had said so I sought out this

curiosity, this book-as-the-author-wrote-it and discovered that

L’etranger led up to the following: “Pour que tout soit consommé, pour

que je me sente moins seul, il me restait a souhaiter qu’il y ait

beaucoup de spectateurs le jour de mon execution et qu’ils m’accueillent

avec des cris de haine”

“Cris de haine”—I was sunk, felt sucker punched, ashamed, held the

novel in my hands as though it were something I could conceal, evidence

that might be buried.

I was wrong about Camus, wrong about all of my passionate rhetoric—my

reasons why execration wasn’t hate, hate wasn’t execration may have been

true but meant nothing now, my insistence on “howls,” my disdain of

“cries,” showed me to be a fool caught up in my own interpretative

subjectivity.

It was as though I had never even read Camus.

***

But of course, I had never read Camus, not until that moment and even

in that moment I was not reading Camus, simply looking at words in a

language I neither spoke nor read—if not for having already seen the

words in translation, the entire thing would be a cipher.

Still, the superficially jarring difference between what I had first

read, had so insistently identified as Camus, and what Camus had

actually said, turned me inside out.

I could not let go of Gilbert, of what I felt about this phrase work,

how I understood the novel, how I understood myself with regard to

it—what Ward said was not what Camus said though I could see for myself

that it was.

Yet, was it?

“Cris de haine.” Cris—“cries” was evident—Haine—“hate” was

evident—but surely in the combination of the two was some sound of

“execration,” surely there was some quirk to the spirit of the

expression that would demand not so much a literal French-English

dictionary insertion but a felt comingling of meaning and linguistic

nuance. I spent awhile in such forlorn, flailing about thought, trying

to cram the words I preferred into the strings of letters in French,

these meaningless jumbles that were words but to me were no words at

all.

***

I first came across L’etranger under the title The Outsider while on

a trip to Ireland—it was a little edition, lovely, and to boot it had a

translation I’d never come across before, this time by Joseph Laredo. I first came across L’etranger under the title The Outsider while on

a trip to Ireland—it was a little edition, lovely, and to boot it had a

translation I’d never come across before, this time by Joseph Laredo.

I’d never heard the piece called anything but The Stranger—it had

been a decade since my first encounter and only this one title had ever

been uttered by anyone I’d met who knew the work, in anything I’d ever

read about it.

Idly flipping to the end of the edition, out of habit, I found that

Laredo had written this: “For the final consummation and for me to feel

less lonely, my last wish was that there should be a crowd of spectators

at my execution and that they should greet me with cries of hatred.”

***

Hate. Hatred. Execration. I set the words side-by-side—‘execration’

was clearly the odd duck, but what was to be made of these other two?

Was hate, hatred? It seemed to me, no, decidedly not.

Hate seemed an abstraction, a universal, something unformed to

individuality; hatred seemed this abstraction filtered through

individuals toward some object in particular, hate-with-direction; and

in the meantime the only definition I’d come across for execration

aligned it to a curse, a denunciation, an active will to damn. But these

were wildly different sentiments—to be met with unformed “cries of

hate”, confronted with an ultimate abstract expression was not the same

as being met with personal “hatred,” with repugnance over one’s own

actions, one’s own being and neither of these were the same as being met

by crowds of people literally cursing, damning, demanding some eternal

form of disgust be visited on another. “Hate” could indicate that once

Meursault was killed a balance would be restored, “hatred” that a

particular justice had been settled, a slight reconciled, and

“execration” suggested that the vitriol would follow the dead man

forever, define him, that his death was not enough, he needed to be sunk

with a weight that would drag his corpse ever deeper and deeper in some

abyss.

No, it wasn’t just the words themselves—the novel was entirely

different dependent on this final sentiment.

It couldn’t after all, be said that the ending could run like this:

“In the end, facing the end, all that I needed to hope for, all that was

required for sense, peace to be made of it all was that on the day they

dragged me through the courtyard to my death I find the streets empty,

soundless, no eyes falling on me, no sound of voices, nothing but the

progress of my own breath.”

Though couldn’t it?

This was not a translation of Camus, of course—even in my

mono-linguistic understanding of the world I knew that—but would it

alter the novel? If someone read every word leading up to this

statement, what would they come away with?

***

What had I come away with?

I felt, again, as though I’d never read the book. What had happened

in it, what had it meant?

To find some grounding, I approached the question from the angle that

interpretation is on the part of the reader, it means something

different to each of us—yes, certainly, any six-year-old could tell me

that.

But, again—this took for granted the original, that if I had read

L’etranger, my interpretation was just the same as anyone else’s, of

equal value, so to speak. But I had never read L’etranger, I had read

The Stranger—I had read two The Stanger and one The Outsider.

Camus had written the novel, not Gilbert, not Ward, not Laredo, but I

had read only Laredo, Ward, Gilbert, never Camus.

I thought of it this way: If I gave my interpretation of Plato’s

Allegory of the Cave to someone, though in my heart I may feel I was

imparting it as it was intended, certainly I was not—someone else’s idea

filtered through a third-party does not equal the original person’s

point-of-view and my further interpretation is all the more removed.

But did this mean, by way of reversing the logic, that in fact the

actual statement of Camus must be none of the words I was

investigating—were they, all of them, extrapolations, incapable of

leading me to the statement of the author, incapable truly of anything

but leading me further away?

Perhaps.

Or was it true that one of them could be the statement as the author

had made it, even unwittingly?

This consideration seemed off, seemed far too semantic—one could not

accidentally express the same as someone else, one could not express the

same as someone else, period.

*******

Of course , I had always accepted this as true—that an author cannot

expect people to literally understand them, must be aware that they are

writing something so deeply coded that its only purpose is to beget

individual response in multiple, a different interpretation for each set

of eyes, for each mind—the thing the reader reads is not the artist’s

novel, and the act of reading, in the end, is entirely separate from the

act of interpreting.

*******

But do I think that?

Look at it this way—hadn’t I been discussing Plato’s allegory a

moment, ago? Assume that Plato imparted the idea to me, but I could not

follow it, that when I tried to explain it back to him, I garbled it.

Then, let’s assume some other party explained it to me and they did so

in such a way that I understood it, could repeat it back no trouble—did

this mean I understood what Plato had to say, or would Plato have to

hear me and then say he approved?

Taking matters to such extreme rhetorical is ridiculous, of

course—according to this spin, the only way to express the allegory

would be to repeat it, verbatim. In fact, alteration, interpretation is

central to understanding, when looked at through this filter—it is a

requirement that I paraphrase, repeat in different words, synthesize the

idea until it is, so to speak, my own.

***

Yet, to what end?

Following this line of thinking, my above, completely altered

replacement of Camus’ final statement could, indeed, be a way of

synthesizing the novel, understanding it—understanding through

interpretation, even through interpretation that produces a different

object.

What did Camus write, after all? He wrote a novel that was an

expression of his idea—in this sense he was Originator—but certainly he

was not writing of ideas that were his origin, but was synthesizing all

manner of input—and in this sense Interpreter.

Yes, I liked this—and again it felt something I ought to have picked

up in elementary school. This seemed sound enough—the interpretive

aspect was present in originator, was necessary to synthesize

originator’s interpretation and so the actual content became, in a

sense, irrelevant as it came to strict sanctity, strict adherence to the

individual expression of the author—Camus was irrelevant to

understanding Camus’ work, because Camus’ work was only an investigation

Camus was making, he had crafted an object to consider that he was no

authority on.

***

I will admit that in my most experimental mindset, in my most

abstract philosophical stabs at understanding literature, I often think

that all work should be translated and only the translations should be

read—even translation within a single language ( translation of

synonyms, I call it). An author should turn his work over to another

party and this party should paraphrase every sentence, re-write what

they see using different words, attempting to render the same thing they

saw through a means that must superficially be different—only these

different words should be explored by readers. There should be an

admission on the part of the artist that it isn’t their words they want

explored, it is the exploration they have begun they want continued.

I assert this in these moments, because this seems to me the

inevitable result of reading, no matter the action of the author, it

seems a necessary, almost mystic acceptance.

In earnest I ask myself—if the artist insists on the audience

interpreting through their exact words, aren’t they, in the end, asking

that their words, exclusively, and not even what the words may represent

be explored?

And to this I answer (as earnestly as I can manage) that there is no

natural insistence on the part of reader that the words they read be

those of the author. No. I can name countless works—many of them most

formative to me—that in the above questioned sense I have not only never

read but would be incapable of reading.

***

I confess, writing this now, that throughout the whole tracing of

this little history—this progress of my personal time spent with Camus

and others who I feel have gotten far closer to him than I—that I have

felt a creeping disquiet not based on anything I have to this moment

discussed. What I find unsettling is that I know none of these personal

discoveries, none of these observations of the importance-of-nuance, the

shattering-alteration-of-synonym, the questionable-sanctity-of-original

are unique to me. Even as I pulled copies from the shelf to make certain

I was setting down quotations correctly I see Translators’ Notes,

Translators’ Introductions—even the most cursory search of commentary,

critique, casual-reader opinion about Camus, Meursault, the

confrontation with the absurd will lead to countless versions of the

same investigation, give or take some quirk of tone, some quality of

conclusion.

I feel horribly un-unique for my honest appraisal of my thoughts over

something I have read and wish I could set down something subtle, new,

unheard, unconsidered—I wish through some cobbled together semantic I

could be the one to define L’etranger even moreso than can Camus.

I wish I could look at the page and see “Alors, j’ai tire encore

quatre fois sur un corps inerte ou les balles s’enfoncaient sans qu’il y

parut. Et c’etait comme quatre coups brefs que je frappais sur las porte

du Malheur” and have no idea, no idea at all what it is saying.

|