Of fidelity and betrayal

By Dilshan Boange

‘Fidelity’ would seem a poetic anomaly in the present world we live

in, a beautiful notion worth romanticising, but distant to the socially

prevalent norm, and almost a myth. ‘Betrayal’ would be the point of

fidelity’s death, its antithesis. Though generally one would read the

words ‘fidelity’ and in juxtaposition to it, ‘betrayal’ within the

context of conjugal connotations or committed relationships between

lovers, Czech born novelist Milan Kundera propounds a perspective on

these two words in his highly acclaimed work The Unbearable Lightness of

Being which transcends the common placement attributed to the notions of

fidelity and in relation to it, ‘betrayal’.

|

|

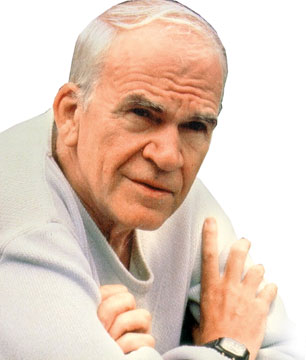

Milan Kundera |

In part three of the novel in the section titled ‘A Short Dictionary

of Misunderstood Words’ Kundera presents a rendering of how these two

words may be understood by explicating how two characters, a man named

Franz and a woman named Sabina, perceive them subjectively in connection

with their respective experiences in life. Franz and Sabina are lovers;

he is an academic and she is an artist.

Cemetery

They are in an illicit love affair, and the understanding that each

has of these words is not strictly built on the lines of sexuality as

the demarcation where transgression from fidelity to ‘infidelity’

through betrayal is clearly visible. Rather it is an emotional landscape

that Kundera presents related to the ‘world of experience’ each connects

with and is shaped by.

Firstly, the author describes what fidelity means to Franz and how it

came to be assigned its values and influence his life and perceptions.

Franz’s conception of fidelity is rooted in his affections to his mother

and how being a companion to her in her times of grief and cherishing

her memory constituted the foundation of what he understands as

fidelity. Kundera narrates it.

“He loved her from the time he was a child until the time he

accompanied her to the cemetery; he loved her in his memories as well.

That is what made him feel that fidelity deserved pride of place among

the virtues: fidelity gave a unity to lives that would otherwise

splinter into thousands of split-second impressions.” (p.86-87).

It appears that to Franz, the root of fidelity is of a filial basis.

It is this filial love and devotion which forms his outlook of what

fidelity could mean and be sourced it to his world of experience. When

Kundera speaks of a ‘unity’ being the outcome or function of fidelity as

a result of being in one’s life, it appears that ‘fidelity’ acts as an

adhesive that instils and maintains cohesion in one’s life.

In that sense, fidelity is a ‘cement’ that holds a relationship, be

they with a physically living person, or even something as metaphysical

as a memory. Fidelity cements what would otherwise be estranged in the

blink of an eye and renders our conceptions of ourselves in relation to

others, as meaningless.

What then of ‘betrayal’? It is arguably ‘transgression’ in the act,

given a physical dimension if one were to view it from a point of sexual

indiscretion. Yet how does Kundera present a perspective on ‘betrayal’

narrating the lives of Franz and Sabina? While Franz believes that

fidelity, based on his subjective understanding and interpretation of it

would be charming to his paramour, it turns out to be the very opposite

to Sabina. She finds the idea of fidelity unpalatable, and is not

enchanted by it. The reason being, what became representations of

fidelity to her, in her ‘world of experience’ was highly disagreeable.

Oppressive nature

What fidelity meant to Sabina was of a more oppressive nature which

interestingly is also based on filial sentiments. However it is not of a

positive nature unlike that of her lover Franz. Observe how Kundera

presents the grounding of the term fidelity in Sabina’s world of

experience.

“The word ‘fidelity’ reminded her of her father, a small town

puritan, who spent his Sundays painting away at canvases of woodland

sunsets and roses in vases. Thanks to him, she started drawing as a

child. When she was fourteen, she fell in love with a boy of her age.

Her father was so frightened that he would not let her out of the house

by herself for a year. One day he showed her some Picasso reproductions

and made fun of them. If she couldn’t love her fourteen-year – old

schoolboy, she could at least love cubism. (p.87)

Thus it is evident that ‘fidelity’ connoted a negativism in Sabina’s

mental track based on the oppressiveness she experienced, especially at

a point in life when she was awakening a deep emotional aspect of

herself. The paternal impositions that restricted her movements stood

for ‘fidelity.’ The puritan attitude of her father, she very probably

found disagreeable, was a strand in the larger fabric of fidelity. As

was the lack of appreciating expressionism beyond the traditional forms,

which is very arguably what the scenario with the Picasso reproductions

is meant to convey. In this context Picasso’s expressionism would stand

for the breaking of orthodoxy, and finding a freedom not allowed by the

established order.

The restrictiveness would have been her father’s way of holding

fidelity within their folds. To prevent a possible transgression was to

be ‘faithful to the old ways,’ and thus the ‘fidelity’ her father had to

his ideals was like Franz’s attachment to his mother and after her

demise, the memory of her.

Clearly there is a great contrast in the way in which the two have

had their conceptions shaped on the meaning of the same word owing to

the difference of filial associations that epitomised to each an ethos

of ‘fidelity’. And it is through Sabina’s revulsion to ‘fidelity’ that a

perspective is brought to the reader on ‘betrayal’.

Conception of betrayal

Firstly, in the section of the novel that is discussed in this

article, Kundera says that Sabina was “more charmed” by the notion of

‘betrayal’ than by fidelity. And the author enters the line of

discussion on expounding Sabina’s conception of betrayal by saying that

when she left her parental home for Prague she was euphoric that she

could then betray her home. This feeling of wanting to betray the

establishment and thereby derive some satisfaction is clearly rooted in

the desire for ‘sweet revenge’. The young girl who felt oppressed and

deprived of pursuing her heart’s desires feels there would be

gratification for blatantly and unapologetically transgressing the

borders that were imposed by ‘fidelity’.Kundera provides us a brief

theorem on ‘betrayal’ by looking at what it means at a conventional,

mundane understanding and then the subjective perspective of how it is

perceived by the likes of Sabina.

Betrayal

From tender youth we are told by father and teacher that betrayal is

the most heinous offence imaginable. But what is betrayal? Betrayal

means breaking the ranks. Betrayal means breaking the ranks and going

off into the unknown. Sabina knew of nothing more magnificent than going

off into the unknown.”(p.87) Therefore, in relation to what she

understood as ‘fidelity’, ‘betrayal’ would be far more appealing as it

would break the bonds imposed by fidelity and allow a sense of

liberation by ‘breaking the ranks’ as phrased by Kundera.

The sense of adventure and liberation that was desired by Sabina

could not be found in what would probably be seen as ‘the confines’ of

fidelity. And so she was not enchanted by Franz’s professing of

fidelity, for it was what ‘betrayal’ had allowed her in life, as an

artist who had a rebellious leaning in her that she found fulfilling.

She found her rebelliousness an alluring trait in herself. However this

does not say that through ‘betrayal’ Sabina found the satisfaction she

was longing for.

After the death of her mother, Sabina’s receives news that her father

had taken his life out of grief, only a matter of days after the

funeral. It is at this point that she questions her stance on fidelity

and betrayal from a point of emotion driven contemplation.

Pangs of conscience

“Suddenly she felt the pangs of conscience: was it really so terrible

that her father had painted vases filled with roses and hated Picasso?

Was it really so reprehensible that he was afraid of his

fourteen-year-old daughter’s coming home pregnant? Was it really so

laughable that he could not go on living without his wife?” (p.88)

This reviewing of her beliefs incited by the loss of the father shows

Sabina’s latent fidelity to her father from a point of filial affection

despite his restrictiveness in her youth which impelled her to seek joy

through betrayal. And the father’s suicide can be viewed as indicative

of his fidelity to his wife, without whom his life would probably seem

to lack unity and cohesion. The effect this dilemma causes Sabina to

seek betrayal once more, this time of what she had founded for herself.

“And again she felt a longing to betray: betray her own betrayal. She

told her husband (whom she now considered a difficult drunk rather than

an eccentric) that she was leaving him.” (p.88) In such a case as what

Kundera presents in the afore lines, it seems evident that out of guilt

and remorse Sabina now believes that betraying herself will punish her

the same way she believed she exacted revenge from her father through

‘betrayal’.

It is probable that through such means she seeks to repair the damage

done and rekindle fidelity. Her second betrayal may have seemed to her a

manifestation of fidelity. But, it is to the contrary that Kundera views

the actions of the impetuous Sabina.

“The life of a divorcee painter did not in the least resemble the

life of the parents she had betrayed.

The first betrayal is irreparable. It calls forth a chain reaction of

further betrayals, each of which takes us farther and farther away from

the point of our original betrayal” (p.88) Thus it is evident that

Sabina cannot redeem herself through another act of betrayal, but only

deepens her enmeshment in the chain reaction that may in a way binds one

to live in a continual betrayal of one’s ideals.

In the context of this discussion it may seem that fidelity poses its

share of restrictions and impositions that would be definitive of

‘fidelity’. And the need to oppose this ‘bondage’ to explore beyond the

boundary, results in ‘betrayal’ which may be a liberating act.

Yet one must realise that once committed, ‘betrayal’ cannot be undone

to restore fidelity. Thus the liberation one may seek from the folds of

‘fidelity’ (as conceived by Sabina) comes at a great cost, which cannot

be recovered. |