|

Meya Thuwakkuwak Novay:

A top satirist in the making

By Dilshan Boange

I first encountered the talent Chamila Priyanka’s had to offer the

realm of Sri Lankan theatre in the New Arts Theatre or the NAT as it was

commonly called, in Colombo varsity. That was when I was an undergrad in

the Arts Faculty and Chamila was my batch mate.

|

Chamila Priyanka |

At the start of our freshman year I knew him as simply another face

on campus. But in 2005, in our freshman year itself, on seeing his short

play Oyai Mamai Thaniyama (You and I alone) at the NAT I realised how

remarkable a dramatist this quiet and unassuming person is.

I enjoyed that short play tremendously. It had me in stitches,

roaring with laughter. Those who were present that day heard an

unusually sharp, robust stream of laughter, which on recurring from the

audience at other comedic plays staged later on at the NAT, got dubbed

‘the horn’ by some who were greatly amused by it. And thus as time went

on there were times when batch mates of mine said they knew I was in the

audience watching a play that they watched since they heard ‘the horn’

erupt from the audience.

It was Chamila’s Oyai Mamai Thaniyama that elicited that fulsome

laughter of mine to erupt in the NAT for the first time. His power to

script and direct elements of comedy is exceptional. A day or two after

watching Oyai Mamai Thaniyama I had my first chat with Chamila.

I went up to him and expressed how much I enjoyed his production. I

professed I was a fan of his work. I congratulated him wholeheartedly

and sincerely wished him success in his craft. That made way for what

was a general familiarity to grow into a friendship over the course of

our undergrad days.

Prowess

Chamila scripted and directed two works of theatre after Oyai Mamai

Thaniyama. Che Saha Juliet (Che and Juliet), which I watched in the NAT

during our undergrad days in 2007, and Cricket Gahanna Enawada? (Coming

to play cricket?), which was after passing out of campus, which I

watched at the Punchi Theatre in Borella. Those plays spoke of Chamila’s

prowess as an artist. His mettle for originality is marked with story

concepts that are inextricably contextualised in Sri Lankan

sensibilities.

And no, his plays aren’t for ‘cheap laughs’. There is a pulsating

vein of satire that forms the blood and bones of his plays. His works

are critiques of our times. They have intelligent colloquial engagement,

shunning garbs of pseudo intellectualism.

Occupying seat Q-7 in the gentle darkness inside the Lionel Wendt

auditorium on August 20, I watched Chamila’s first feature play -Meya

Thuwakkuwak Novay (This is not a gun), gain colour, form, and flesh.

When looking over the whole of the work and comparing it with his short

plays there is no doubt that the political critique he wishes to bring

to the public discourse as an artist, now, has a somewhat fiery pulse.

There is sharper protest and outright outcry against autocracy now

more than before. I felt, perhaps there is some jaggedness to the

aestheticism in Meya Thuwakkuwak Novay if one considers the velocity of

the ‘political tones’ it contains as compared to Chamila’s previous

plays. But then one cannot chirp like a bird and hope to create a

hubbub.

The content of the play contains a vast array of elements for

elucidation. Meya Thuwakkuwak Novay has a ‘loaded text’. However since

an exhaustive discussion on the play in its entirety is simply not

possible, I shall focus on some key aspects related to the theme and

content of the story and some attributes related to performance factors.

One of the hard hitting themes of Meya thuwakkuwak novay builds on

the thesis -‘the power of the saffron robe’; a reality that no Sri

Lankan can be unfamiliar with and still practically claim to be Sri

Lankan.

The plot, at elementary level, has a young Bhikkhu who sneaks out one

night intending to secretly disrobe, leave the order and enter a

layman’s life, who encounters a man who is of an unsound mental state

and over the course of a nightlong journey which metes out a chain of

events decides to return to the folds of monkhood which will offer him

better security from a world that seems maddening.

Saffron robe

The saffron robe holds an incomparable position of exaltedness in Sri

Lanka. A factor that defines our national ethos since time immemorial.

While the life of a clergyman demands that certain layman pleasures are

given up, the clergyman’s position is accorded privileges and deference

which a layman cannot claim.

The Bhikkhu who disrobes and finds that leaving the sacred saffron

robe strips him of all privilege realises that life as a layman may not

be as rosy as he may have envisioned.

|

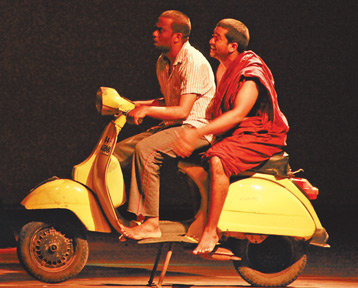

A scene from Meya Thuwakkuwak Novay |

What was clearly observable in Meya Thuwakkuwak Novay is that it

overtly critiques the Buddhist establishment in Sri Lanka with regard to

what may be thought of as ‘commonplace allegations’ which basically

claim that some Bhikkhus pursue worldly pleasures.

The play openly views the police force as one that may willingly

subject itself to the sacrosanct nature of the saffron robe and enforce

the law between the clergy and laymen.

The manner in which the same person is treated when donning the robe

and when wearing layman’s clothes shows that striking factor which works

to the dismay and disadvantage of the Bhikkhu who planned to enter a

layman’s life.

‘Do not underestimate the power of the saffron robe. Do not abuse the

sacred robe of the Buddhist clergy’ seems to be an advocay Chamila has

woven into the text of the play. Although it may be very easily

decipherable to read the play in the context of an antiestablishment

work, I feel there is a vein in the play which seeks to silkily move

into the average Sri Lankan’s conscience that the sanctity of the

saffron robe must be guarded against acts that would lower its esteem in

the eyes of devotees, who would get disillusioned when they see a member

of the venerable Sangha in an unbecoming manner.

Perhaps there lies the playwright’s statement of patriotism which

speaks of a sense of nationalism beyond mundane politics and reaching to

the deeper roots of our cultural being. Chamila, I feel, thus makes an

appeal through the subtext of the play to both the religious

establishments and laymen.

Disgruntled

While it is all too commonplace to expect disgruntled laity who gets

disenchanted whenever a clergymen errs in conduct, one must also give

consideration to the fact that a life in priesthood is not an easy task.

Fighting temptation from worldly desires is easier said than done. And

while perhaps society may be given to cynically look at those who leave

priesthood as near degenerates, it should be borne in mind that during

the time of the Buddha there had been a Bhikkhu who had left and

re-entered the order repeatedly for seven times, and had finally become

an Arahat.

It must be noted therefore that although the Bhikkhu who secretly

disrobes to leave the order in Meya Thuwakkuwak Novay is more or less

shown as somewhat an unwholesome character, the fact that he, although

perhaps out of convenience, states at the end, is going to become a

Bhikkhu and thereby effectively rejoin the order, shows there may be

hope for him yet.

Perhaps the reality of the world he saw with all its myriads of vices

and dangers will propel him to sincerely seek shelter in the order of

the Sangha and truthfully seek to tread on a path of spiritual

development.

The linearity of events tends to create our chronologies, if ‘time’

was to be measured by means other than watching the hands of a clock or

the change of the direction of the sun. Meya Thuwakkuwak Novay brings

this theorem of how time can be seen to manifest in relation to the

motion of physical bodies, in very simple and practical depictions of

interplay between characters and their actions. Thus Chamila brings a

dimension of the ‘theory of relativity’ to the Sinhala stage.

The science that Chamila brings to the stage is not couched in

grandiloquence but touches the sensibilities of an average person. If

you aren’t in motion, then you are stationary. And if you believe

objects are ‘moving towards’ you, the logical explanation is that at

least one of the two is in motion, but which one exactly may be

debatable.

The young Bhikkhu who wishes to exit the order is desperate to escape

the landscape that he is caught in. The jubilance in his face as he

believes the scooter he is mounted on is in motion shows how he

intensely desires to believe he is going forward, towards a new horizon,

leaving behind his past.

There is a great deal of symbolism involved in how Chamila has

crafted the simple scenario of how a motorcycle stays put against an

unchanging landscape, while a belief, or at least a desperate desire to

be in forward motion by the riders is made a central investigation in

the fabric of the play.

There is in that aspect of the story a serious ontological

investigation about existence and reality. There is in that substance of

the story an entreating facet of ‘absurd theatre’ which is however

endearingly sculpted to meet a Sri Lankan viewer’s embrace in terms of

plotline, story setting, and dialogic form. The absurdness in Meya

Thuwakkuwak Novay however, cannot be called to draw its mettle from

strands of Ionesco or Becket. Meya Thuwakkuwak Novay truly shows a Sri

Lankan creative pulse for origination.

Absurd

This play is not directly classifiable as a realist play in terms of

genre. But neither can it be called a work that fully befits the

‘theatre of the absurd’. The scenario depicted at the outset seems very

realistic enough to anyone. The reply given by the vagrant-like man

rummaging through the heap of wayside garbage, that he is looking for ‘a

job’, ‘employment’, hints at an ingredient of the absurd, which is

potent with symbolism while the revelation that the man is of unsound

mental health sets the status quo to create a veneer of realism into the

story’s premise.

|

Another scene from the play |

When policemen are lulled to sleep every time a patriotic Sinhala

song is played on the portable radio, there rises a vein of the absurd

as opposed to the realist. When a woman with a child who arrives on the

scene suspected to be the malefic female spirit from Sinhala folklore

Mohini, an element of the fantastic comes into play. But when she

reveals to be a streetwalking prostitute, the dimension of realistic

plausibility sets in.

The symbolism in Meya Thuwakkuwak Novay is not overbearingly

protuberant. It is tasteful. When the plain-clothed man who was before

donned in the saffron robe tells a blissful drunkard that the latter’s

drinking buddy ‘Dharme’, who apparently had been around a moment ago but

seems to have vanished, is unlikely to be found, because the two topers

had been discussing politics on the way from the bar, a chilling message

wafts into the air.

When deciphering the structure with which the play has been woven in

terms of how its different elements play out to deliver its ‘politics of

theatre’, one must take to account that Meya Thuwakkuwak Novay is

layered in its ‘meaning value’. The characters offer their respective

doses of entertainment to the laughter seeking audiences through their

interplay with each other while also possessing the capacity to be stand

alone symbols.

The man of unsound mind seems to be the only person manifesting

humanistic values which are sadly brushed aside due to the

‘inconvenience and impracticality’ to the person who desires his

services to drive the motorcycle.

Policeman

The policemen while standing to be symbols of authority also

represent their humaneness, which can of course have both positive and

negative attributes. The prostitute who is clearly a destitute shows how

she too is human although the general tendency would be to see her in

the light of a ‘nonhuman’ – the image of Mohini taking a symbolic value

here to parody ‘dehumanisation’ of women of the street.

The drunkard who merrily ambles homewards may seem a worthless boozer

who squanders his money when he ought to spend it for his wife and

child. Yet the same drunkard extends to the disrobed Bhikkhu, an

ordinary looking young man, whom he had encountered in the dead of night

on the open road, to spend the night at his house if the young man has

no place to go.

It shows the heart warming humaneness that Sri Lankans like to

consider as part of the ethos that defines our unique sense of ‘civic

mindedness’; to be unselfishly giving and generous to even a stranger

who may seem in need of a helping hand.

The spirit of hospitality that assures social security among ordinary

people. The kind of generosity that says, ‘my home is yours, if ever

you’re without shelter.’

The pile of garbage that never leaves the ‘escapees’ perhaps

symbolises society today which has degenerated to rottenness. It is in

that heap after all they find some of the most intriguing things. And

all forms of employment must be ultimately sought out whether appealing

or not, in society. The cannon, though silent, has a presence that

creates a menace in the subconscious of the ordinary man who is given to

wonder what its purpose is.

The only man who seems logical and laudable is rendered a voice that

is unfit to emulate on account of being indicated a mental patient. The

play is thus a dark comedy which does not however drive its audience to

dismalness by projecting the darkness overbearingly. Sri Lankans don’t

like it that way. Too bitter a truth cannot be hoped to be digested when

forced down our throats. We have to be cajoled into taking our

medicines. Chamila Priyanka is a theatre practitioner who understands

the average Sri Lankan theatregoer’s pulse.

Commendable

I must wholeheartedly applaud the director for having a chosen a

highly talented young pool of actors to take on the characters. Each of

them delivered their role commendably to display an evenly balanced

spectrum of acting talent on the boards that evening. The vision of the

director can be optimally achieved only if the casting can be done to

complement the roles in relation with the innate attributes of the

players. Good actors are not easy to find. In this regard I feel the

casting was done excellently.

Special mention must be made of Mayura Kanchana whose performance as

the mentally unsound man was brilliant, as were Dilum Buddika as the

Bhikkhu and Kanishka Fernando as the drunkard. The cast comprised Mayura

Kanchana, Dilum Buddika, Kanishka Fernando, Pramodh Edirisinghe, Yashoda

Rasanduni, and Anjana Premarathna.

The entire production team should be proud of what they achieved with

Meya thuwakkuwak novay. The show was made possible I understand, due to

the financial assistance from a collective of theatre supporters named

‘Naatti seettu’ led by Dr. Udan Fernando of the Centre for Poverty

Analysis (CEPA) whose efforts must be appreciated in this regard.

During those undergrad days in the Colombo varsity’s Arts Faculty,

there was at that time a pool of students who were involved with the

mass media and performing arts in various ways. There were a host of

Sinhala and English medium TV broadcasters – Buddhini Pathirana, Imani

Perera, Nishani Pigera, Anouk Thilakaratne, the late Madhawa Ganegoda

who initially hosted Derana TV’s ‘Waadapitiya’, Niranga Wijesuriya,

Buddhiprabha Kulatunga, as well as yours truly! There were painters,

dancers, vocalists, and musicians.

There were a number of thespians from various batches, and my batch

alone had three playwrights cum directors who displayed their talents as

undergraduates.

They were Indika Bandara Abeykoon, Prabath Kapurubandara and Chamila

Priyanka. While it saddens me to see that not everyone who found an

opportunity to bring out their talents in the arts and mass media back

in those days, made efforts to continue engagement in those fields after

leaving campus, it is heartening to know that from among the three drama

directors mentioned, Chamila is committed to carve out a name as a

theatre practitioner.

And I believe that what can be seen in Chamila Priyanka, through Meya

Thuwakkuwak Novay, is the making of Sri Lankan theatre’s top satirist of

the new generation. |