Villagers too scaled the heights

By K.D.M Kittanpahuwa

The other day I read Goldsmith's Deserted Village in which he said

‘Where wealth accumulates, and men decay;

But a bold peasantry their country's pride

Once destroyed, can never be supplied,’

this prompted me to write a few lines about my own village. Today, we

witness the last vestiges of fast vanishing villages. My village is no

exception. The peasant and the temple which formed the nucleus of the

village have lost their pristine glory.

The bhikkhu was hero-worshipped. His commanding stature made him the

benefactor, arbitrator and the symbol of social cohesion of the village.

In distress, people sought his advice and his prescription had a

soothing effect on them.

Values

Apart from him, the Vedamatmaya (Physician) Kattanndiya (Exorcist),

Gamey Ralahami (Village Headman) and Iskola Mahattaya (Teacher) were the

most respected.

Values which bound the villagers together had a strong influence on

their lives. The villagers, irrespective of differences in social life

were simple, accessible and spartan. The unsophisticated villager had no

pretension for doctorates from Harvard or Michigan and yet they

succeeded in life. Values which bound the villagers together had a strong influence on

their lives. The villagers, irrespective of differences in social life

were simple, accessible and spartan. The unsophisticated villager had no

pretension for doctorates from Harvard or Michigan and yet they

succeeded in life.

Stress or hypertension were unknown to them. Their sturdy physique

needed no physiotherapy or painkillers. As Buddhists, their lives were

conditioned by the three major elements, Jathi, (Birth), Jara (Decay)

and Marana (Death). They only seldom missed a Poya to observe sil. If a

tragedy occurs, they would console themselves with a few words

“Anichchey Dukkhe Sansaray” which basically denote impermanence in all

living beings. Despite the religiosity there were those who resorted to

violence for petty issues such as a disputed boundary or a fence. As

much as the villagers were quiet, a sudden irruption might result in a

single or perhaps even double tragedy.

Ignorance

The villagers probably due to ignorance believed more in the

Kattandiya than Vedamahattaya in curing diseases. If one falls ill, the

Kattandiya was promptly sent for instead of the Vedamahattaya, whose

prescription was “noolak bendeema” - a process of propitiating the

spirits to ward off the evil influence on the patient.

Three people, Dala Kattandiya, Emis Atha and Kalati Appuhamy who are

dead, haunted my childhood memories.

They were part and parcel of the lives of villagers. Dala Kattandiya

earned this nick name due to his irregularly positioned teeth. The

miscreants called him ‘Dalaya.’ His authoritarian, yet friendly tone

tells a different story – that he was the lord of all that he surveyed.

His successful career running into decades was blasted when he

accepted a daring challenge to save a serious patient from imminent

death. He made the relations of the patient believe that the power of

his mantra could even resurrect a dead man! His prescription was that he

would exorcise the evil spirit, the patient was possessed of.

In the midst of his devil-dancing around midnight, the critically ill

patient after a few gasps breathed her last. Dala Kattandiya and his

assistants were mercilessly beaten by the people.

A few hours later they heard someone beating a drum afar. They found

the drum-beater who escaped the ordeal of beating was calling for help

from a deep, abandoned well. This was poor Dala Kattandiya's waterloo!

The other person who adorned the village was Emis Atha who was still

vibrant in his fifties. He was a wood cutter by profession.

His expertise lay in his correctly guessing the age of any tree. It

was because of his ‘professionalism’ that he was nicknamed ‘Professor’

which he accepted as an honour for him. His two sons, ‘distinguished’

themselves as carpenters.

Like many others in the village, the two could not overtake their

destiny and ended up as inveterate drunkards-one died prematurely, the

paralysed till death.

He was always clad in amude, (loin cloth) which he dared to wear for

any occasion, perhaps as a symbol of the dignity of labour.

At the end of the day's labour he went to Thotalanga to savour a

bottle of toddy. After a couple of drinks he used to sing his cares

away,

“Aala sula manchi nona saya sobana,

Puraya dala suda balanna thama beriuna”

Amis Atha's end was pathetic. His wife, disoriented between two world

did not show a bit of care or affection for him. His two sons had no

other interest in life than imbibing kasippu. It was a pity to see the

one-time sturdy man with sinewy limbs now reduced to a frail body and

confined to a bed.

As Thomas Gray lamented, “One morn I missed him.”

Pacha Matta, Begal Pedda, Kalati Appuhamy and Kana Charaiya played a

role no second to that of Dala Kattandiya and Amis Atha. They were

notorious for their wily craftiness.

Pacha Matta and Begal Pedda were professional liars. In the

sophisticated art of lying, the two had excelled to be 'Primus Inter

Pares’ - the first among the equals-in the village.

Many an educated person would have been astonished at their

professional manner of concocting stories. If ever there was a land

dispute, the litigants went in search of them to give evidence in

support of them. Such was their expertise acknowledged by their peers.

‘Pacha’ and ‘begal’ broadly stand for lies in local parlance. People at

the village tea kiosk were eagerly waiting for the two busybodies to

listen to their yarns.

One day when the rumour spread that the village headman's cattle were

stolen Begal Pedda bragged, “Nobody in the village could steal anything

without our knowledge.” Within minutes, the headman realised Begal Pedda

had a hand in this foul affair and had beaten him mercilessly until

somebody pleaded on his behalf and the beating ceased.

‘Good riddance of bad rubbish’, the villagers consoled themselves.

Experts

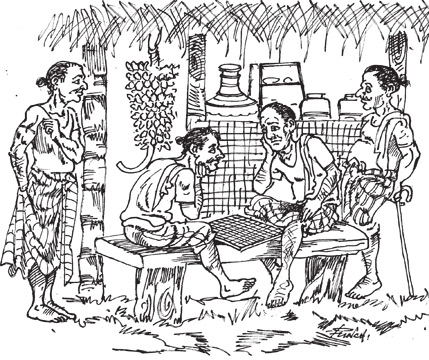

Begal Pedda, Pacha Matta and their chum Kana Charaiya were experts in

the local game of ‘daan edilla'. Early in the morning they would start

the game and continue till late afternoon. Kana Charaiya was an ace

conman who would indulge in some nasty but innocuous thing to earn a few

extra rupees. He was a chain smoker and he would do anything for a

cigarette.

One morning, he fell near the local bazaar pretending that he had

fainted. When the people sprinkled water on his face to help him

recover, he murmured in a feeble voice, “dumak, dumak...” meaning a

cigarette. Such was his patent craftiness.

These were the people who ‘illuminated’ the village. Among the

innocent and peaceful, there were the black-sheep too.

The last notable person in this bygone era was Kalati Appuhamy. Tall

and scraggy and hungry looking with a special bent for pooh-poohing

other religious faiths, he was an ardent Buddhist.

In his arguments with Christian friends, he would advise them to read

Ven. Battaramulle Sri Vibbhuthi Thera's 'Durvadi Herdaya Vidharanaya. He

was unlettered and harmless, yet the neighbours abhorred and never

entertained him, as he was a homosexual – an indelible social stigma in

the village.

He was an excellent organiser of Buddhist pilgrimages and of all

places of worship, Kawatayamune, off Matale, was his best. After

returning from one such pilgrimage, to the surprise of all he related

how he saw a kohila yam (kohila alaya) laid as a foot-bridge across a

small canal. In his own words ‘kohila alayak adantata dala'!

Somewhere in the corner of my village, a land-locked area conspicuous

by its being cut off from the mainstream, was “Anda Manda Doopatha’ –

the Andaman Islands. A few fast-diminishing poverty stricken families,

not more than 20 lived there being somewhat ostracised for no fault of

their own.

They were generally unclean and seldom bathed in the small well

patronised only by their community.

Peaceful

Their lifestyles have no parallel. Marked by charcoal-black teeth

caused by constant betel-chewing, these families were well-known for

their soiled clothes.

Despite occasional irruptions between families the atmosphere was

generally peaceful. Alliya, Vimale -nick-named ‘Dr.’ Wilison and Adau

Goone were some of their names still fresh in my memory.

Much water has flowed under the bridge since then and today there is

hardly any trace of Anda Manda Doopatha caught up in the surge of time.

“All, all are gone, the old familiar faces’ lamented poet G.K.

Chesterton. The overpowering presence of poverty and stagnation took a

heavy toll on these villagers’ lives. Lack of primary education, basic

health care and social intercourse made the lives of these people

miserable.

“Chill penury repressed their noble rage.”

- Thomas Gray |