|

Children are sure to know about the cheetah:

Speed and grace of the cheetah

All

children are sure to know about the cheetah. You would know that it’s

the fastest land animal on Earth with the ability to run at speeds of

112 to 120 km/h (70 to 75 mph), accelerating from 0 to over 100 km/h

(62mph) in just three seconds. The speed and grace of this member of the

cat family have astonished humans and the sight of a cheetah running at

full speed on television never fails to stop us in our tracks. All

children are sure to know about the cheetah. You would know that it’s

the fastest land animal on Earth with the ability to run at speeds of

112 to 120 km/h (70 to 75 mph), accelerating from 0 to over 100 km/h

(62mph) in just three seconds. The speed and grace of this member of the

cat family have astonished humans and the sight of a cheetah running at

full speed on television never fails to stop us in our tracks.

Though these kings of speed don’t live in Sri Lanka, we all know one

by sight. But have you heard of the king cheetah? This is an extremely

rare, regal and strikingly beautiful breed of cheetahs in Southern

Africa. It’s believed that only about 30 of these animals survive today

with only about 10 living in the wild.

Scientists think that about 10,000 -12,000 years ago, at least 99

percent of the world king cheetah population may have died within a

short period, resulting in the population getting as low as one pregnant

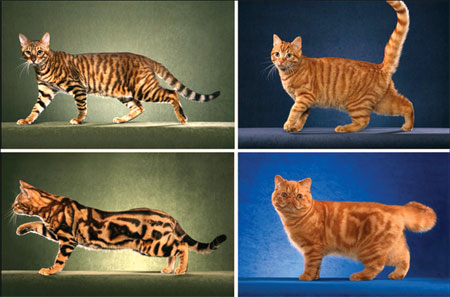

female. The main difference between the king cheetah and the normal

spotted cheetah is in the coat pattern. The standard cheetah’s fur coat

is usually yellow, tawny or golden in colour with a circular spotted

pattern of small black markings, 0.75 to 1.5 inches in diameter,

distributed fairly evenly across its body. The animal also displays the

famous black ‘tear streaks’ down either cheek.

The king cheetah whose coat is pale cream to yellow has a distinctive

patten of spots that run together to form several (usually three) thick

lack stripes down its back, from the crest of its neck to the top of the

tail.

In the king cheetah, spots coalesce into large blotches, and

stripes

develop on the animal’s back |

|

In the king cheetah, spots coalesce

into large blotches, and stripes

develop on the animal’s back |

They also sport dark patch-shaped markings (splotches), irregular in

size and shape along their sides and flanks. Their underside is

generally white. The tear tracks on the face are present in the king

cheetah as well.

The reason for this difference was discovered recently to be a

mutation of the gene which causes the spots in cheetahs. The same gene,

it was found, produces the striking dark stripes on tabby cats and its

mutation causes the stripes in cats and spots on cheetahs to become

blotchy. King cheetahs are the result of two parents with the same

recessive gene coming together (a reason for its rarity) and may occur

side by side with normally coloured litter mates. (See boxed story)

However, they have the same genetic makeup as the common cheetah with

little genetic diversification and problems inherent from inbreeding.

The king cheetah, measuring 1.1 – 1.4 metres in length, 66-85 cm in

height upto the shoulders and weighing 40 – 65kg, is slightly larger

than the common cheetah.

Other rare colour morphs (gradual transformation) of the species

include speckles, melanism, albinism and grey colouration. Most have

been reported in Indian cheetahs, particularly in captive specimens kept

for hunting. The king cheetah is found in Zimbabwe, Botswana and in the

northern parts of South Africa’s Transvaal province. Their natural

habitat comprise savannah and open areas such as plains, wooded areas

and grasslands. While cheetahs prefer to chase their prey on the open

plains, king cheetahs can be found in forests, stalking their meal which

is mostly medium and large-sized mammals. Cheetahs hunt during the day,

while king cheetahs hunt mostly at night. Since splotches are better

camouflage for partially lit environments, the coats of the latter are

better suited to shady forests.

Discovery

A king cheetah cub on a tree |

A young king cheetah cub |

The king cheetah (also known as Cooper’s cheetah) is believed to have

originated from Central Africa, where they were used for hunting. It was

first observed in what was then Southern Rhodesia (modern-day Zimbabwe)

in 1926.

The following year, the naturalist Reginald Innes Pocock declared it

a separate sub-species, naming it Acinonyx jubatus rex (The common

cheetah is classified as Acinonyx jubatus. Rex means king), but reversed

this decision in 1939 due to lack of evidence for a separate

sub-species.

In 1928, a newly dsicovered cheetah skin was found to be intermediate

in pattern between the king cheetah and spotted cheetah and was

considered to be a colour form of the spotted cheetah. Twenty-two such

skins were found between 1926 and 1974.Since 1927, the king cheetah was

reported five more times in the wild.Although strangely marked skins had

been discovered in Africa, a live king cheetah was not photographed

until 1974 in South Africa’s Kruger National Park.

Two cryptozoologists (those who search for and study animals whose

existence has not been proven) photographed one during an expedition in

1975 and also managed to obtain stuffed specimens. The animal appeared

larger than a spotted cheetah and its fur had a

|

A family of cheetahs including two king cheetahs |

different texture. There was another wild sighting in 1986 -

the first in seven years. By 1987, 38 specimens had been recorded, many

from skins.It was consideresd as a separate species until May 1981 when

two king cheetah cubs were born to two normal spotted cheetahs at the

DeWildt Cheetah and Wildlife Centre in Pretoria, South Africa. The

discovery of the recessive gene enabled scientists to breed several

animals in captivity.More king cheetahs were later born at the Centre

and some have even been exported to zoos in other parts of the world.

This centre is responsible for the preservation and present population

of the king cheetah.

Sometimes, this animal is referred to as a ‘DeWildt cheetah’ as a

tribute to the Centre’s successful efforts to preserve and protect this

animal from extinction. The majority of the existing king cheetahs in

the world are descendents of the DeWildt cats.

IT

Cats’ stripes and spots tracked to a gene

The gene that produces the striking dark stripes on tabby cats is

also responsible for the spots on cheetahs, a new study reports. And a

mutation of this same gene causes the stripes in cats and spots on

cheetahs to become blotchy. “Nobody had any idea what the genes were

that were involved in these things,” said Stephen O’Brien, a geneticist

now at St. Petersburg University in Russia and one of the researchers

who led the study. “When the feline genome became available, we began to

look for them.”

Dr. O’Brien and his colleagues published their discovery of the gene,

known as Taqpep, in the journal Science. The findings are based on data

analysed at the Hudson Alpha Institute for Biotechnology, in Alabama;

the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research, in Maryland; and

Stanford University.

Cheetahs that have the Taqpep mutation (and therefore blotches and

stripes) belong to a rare breed known as the king cheetah, found in

South Africa. Tabbies with the mutation are more often found in Europe,

Dr. O’Brien said. In the United States, the striped tabby is more common

The researchers used DNA samples and tissue samples from feral cats in

Northern California, along with small skin biopsies and blood samples

from captive and wild South African and Namibian cheetahs.

The scientists also discovered a second gene, Edn3, that controls

hair colour in the cats’ coat patterns. There is more work to be done in

looking at other genes, and at other cats both domestic and wild, Dr.

O’Brien said. “We’re still fishing around to really unravel the pathways

involved in pattern forming and pigmentation,” he said.

- The New York Times |