The Key - The Japanese novel in Sinhala

Reviewed by Kalakeerthi Edwin Ariyadasa

The heart of mine is

only one.

It cannot be known by anybody else but myself.

1963 poem by Junichiro Tanizaki (1886-1965)

Gentle journalist and bi-lingual author, R.S. Karunaratne, has

addressed an excruciatingly troubling creative challenge. Armed with a

full, responsible and realistic awareness of the formidable of the task

undertaken, he has rendered into Sinhala, the Japanese novel Kagi (Key)

by Junichiro Tanizaki.

From the time this globally-renowned, prolific Japanese

man-of-letters, Junichiro Tanizaki presented it to the public domain,

for the first time in 1956, this novel Key, has always been at the

centre of eddying and swirling controversies. From the time this globally-renowned, prolific Japanese

man-of-letters, Junichiro Tanizaki presented it to the public domain,

for the first time in 1956, this novel Key, has always been at the

centre of eddying and swirling controversies.

Critical accord

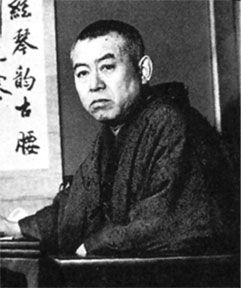

By popular acclaim and critical record, Junichiro Tanizaki, is

undoubtedly among the greatest writers in the long annals of Japanese

literary tradition.

The origins of the Japanese novel, extend to the distant past. The

saga Genji Monogatari (the tale of Genji) is credited as the world's

earliest novel. Written by court Lady Murasaki Shikibu, (978-1031) this

novel of epic proportions, is an intimate narration of life at court.

This historically significant novel was completed around 1011. From then

on, down to our own day, the Japanese novel, has commanded world

attention.

Yukio Mishima, real name Hiranka Kimitake (1925-1970) was nominated

for the Nobel Prize for Literature on three occasions. Yasunari Kawabata

(1899-1972), won the Nobel Prize for literature, in 1968. While awarding

the prize, the Nobel committee cited three of his novels - Snow Country,

Thousand Cranes and The Old Capital.

Prestigious tradition

Junichiro Tanizaki, whose work Kagi (Key) is converted into Sinhala

by R.S.K., is vehemently a product of this sustained and prestigious

tradition of novel writing in Japan.

Tanizaki, was recognised widely outside Japan by the translation of

his work Sasameyuki (Light snowfall-1948) into English, under the title

Makioka Sisters. I still recall this witty social satire, with a

titillating memory.

Translator R.S. Karunaratne, has opted to turn into Sinhala, probably

the most controversial work of Junichiro Tanizaki.

Some critics tend to consider this work to be a sadomasochistic

literary cruise. In essence, this work, explores the dark, unlit mazes

of the underworld of the human psyche. The style of narration that the

author settles for, befits this uncanny, perverse probing to the hilt.

This strange human chronicle is recorded in the form of diary

entries.

Co-protagonists

The work is structured with two equally weighted co-protagonists a

man and a woman. They are an ageing married couple. Each partner keeps a

diary. By definition, a personal diary is a repository of intimate

secrets. The assumption is that what is set down in such a diary is

strictly and exclusively for private use.

|

|

Junichiro Tanizaki |

But, in this instance, there is a bewildering tacit understanding

between the two that the entries are for mutual consumption. The man is

55 and is learned an affluent. The woman is 44, beautiful and seductive.

The man suffers inner pangs, with the unsettling awareness of the

inklings of his failing sexual potency. He assumes that, the diary

entries of his sexual whimsicalities, will erotically arouse his spouse,

transforming her into an ecstatic bed-partner.

The lurid extents to which he takes his fetishistic frenzy are

detailed out in his entry for January 29 (pages 21-25 in the

translation)

The diary entries form the medium of erotic communication between the

two protagonists. A reader may occasionally suspect, that the

clandestine records may harmfully stimulate an untoward erotic fervour.

But, to my mind, to a reader who gets engrossed in this seemingly

lascivious carnal charade may teeter precariously on the verge of the

erotic and the pornographic. But, the author's clinical and

dispassionate approach prevents such an awkward emotional deterioration.

Through all these intriguing entries, the author deliberately leads

the characters towards a shocking finale. The three characters Ikuko,

the wife, Toshiko the daughter and Kimura the lover are all caught up

inescapably, in an intricate web.

Only the disturbing denouement will fully reveal the puppeteer who

manipulated the strings.

Generalisation

The novelist Junichiro Tanizaki tends to make a generalisation. The

average man may be attracted by the idea of concentrating on various

parts of the woman's body. The novelist makes the point that an

emotional transformation to enable holistic love could avert perverse

manifestations.

The work Kagi (Key) is an important document to highlight oblique

ways of human behaviour.

As for the translation by writer R.S. Karunaratne, I have discovered

in it a highly practical use of Sinhala idiom.

In terms of the prefatory note, this is his debut in Sinhala writing,

at book-length. The first effort is quite effective since its style can

ensure reader absorption and reader-appeal. In terms of the prefatory note, this is his debut in Sinhala writing,

at book-length. The first effort is quite effective since its style can

ensure reader absorption and reader-appeal.

Female figure

The cover art may even please Janichiro Tanizaki, because the female

figure may be an approach towards the lady wooed by the writer of

entries.

I really admire the translator's level of word-use, because,

intimate, private and erotically moving situations are communicated with

exemplary restraint in this verson of Kagi.

The tradition of Japanese fiction, especially in its classical

manifestations can be wholesomely instructive to Sri Lankan writers,

when they make an effort to produce novels with a deep human impact.

Writer-translator R.S. Karunaratne could now perhaps turn to

Junichiro Tanizaki's Makioka Sisters, which will prove to be of greater

relevance to the indigenous way of life.

Translators enrich literature. R.S. Karunaratne's Key (Yatura) will

perform that service, quite effectively.

|