New Year is here again! New Year is here again!

By Kalakeerthi EDWIN ARIYADASA

“The sun and stars that float in the open air;

The apple-shaped earth, and we upon it - surely the drift of them is

something grand!

I do not know what it is, except that it is grand!

and that it is happiness.”

- US poet Walt Whitman (1819 – 1892)

Let us all rejoice.

New Year is here again.

Days of joy and happiness are just round the corner.

Time for ardour - Time for feasting -

Time for reunion. It is all here.

Reading the lines above, one may very well wonder why on earth there

should be such an effusive gush over a routine annual event. What has

brought on this fresh flood of enthusiasm for an age-old ritual?

I will explain.

In the recent past, our society has continued to display a steady

alienation from our wholesome traditional practices. A prominent victim

of this distressful negligence is the New Year Festival. Year after

year, our collective zeal and fervour for New Year celebrations have

perceptibly declined.

Over the past few years, commercial interests, electronic media and

print media have effectively prodded the masses awake to the need to

celebrate New Year. Our religious centres - temples and monasteries -

have continued to provide perennial guidance to their communities in the

proper performance of the rites and rituals linked to the New Year

celebrations.

With all that, mass passion for New Year celebrations has been

clearly on the wane. The profound pleasure of the New Year family

reunion has vastly dwindled due to rapid transit. The endless agendas of

the modern generations, their hurry and urgency do not allow them

sufficient soul space to savour the keen human delights of the New Year

festivities. Why I waxed enthusiastic at the beginning of this essay is

because even under those restraints, New Year is here again. With all that, mass passion for New Year celebrations has been

clearly on the wane. The profound pleasure of the New Year family

reunion has vastly dwindled due to rapid transit. The endless agendas of

the modern generations, their hurry and urgency do not allow them

sufficient soul space to savour the keen human delights of the New Year

festivities. Why I waxed enthusiastic at the beginning of this essay is

because even under those restraints, New Year is here again.

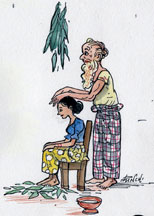

Visual announcement

One will find it extremely difficult to appreciate fully the joys of

New Year celebrations, unless one enjoyed a rural childhood that

resonated to the aura of the New Year festival. The village gets ready

for the New Year, months ahead of the event. The deep red buds of the

Erabadu tree are nature's colourful visual 'commercial' to announce that

the New Year will be with us soon. The sweet warblings of the cuckoo add

a compelling soundtrack to the 'visual'.

The life of the rural community is overwhelmed by the preparations to

greet the 'New Year Prince'. The details they focus on are astonishing.

To quiten the troubling fruit-fly, they employ a ruse. They have a rice

cake (keuma) to attract the fruit-fly, to prevent the insect from

harassing humans. The village community is astir - individually and

collectively - to celebrate this festival, which assumes prime stature

in the national calendar.

Traditionally New Year festivities are held on April 12, 13 or 14

every year. The auspicious hours are calculated in terms of traditional

dicta. Traditional astrology assumed that the sun “travels” from the

Zodiacal sign of Pisces to the Zodiacal sign of Aries, ushering in the

New Year.

This belief must certainly amuse the modern generations. For us, it

is axiomatic that our Planet Earth orbits the Sun, in a non-stop

celestial routine. This space drama has gone on for billions of years.

Our home, Planet Earth and those of us who inhabit it keep on orbiting

the Sun. However, the traditional belief is so thoroughly entrenched,

that we arrange our New Year celebrations on the assumption that New

Year begins with the transit of the Sun from Pisces (Meena) to Aries

(Mesha).

Oldest festival

It must be stressed that as much as the New Year festival is our

foremost celebration, it is mankind's oldest festival too. In man's

earliest days on Earth, he was intimately linked with the processes of

nature. The veering seasons dominated his cycle of existence. Nature was

at its brilliant best in Spring. Clad in green, nature smiled. Streams

gurgled along. Song-birds warbled their rapture. Summer embraced them,

nourishing them with its sumptuous fertility.

Autumn came along. The falling leaves saddened the people, with a

hint of decay. Winter reduced the ancient human into utter helplessness. Autumn came along. The falling leaves saddened the people, with a

hint of decay. Winter reduced the ancient human into utter helplessness.

He was devastated that the God of Nature was dead. People wailed and

wept. In early human cultures, the ancients wept, wailed and lamented in

actuality. They went about mourning. This loss of the nature-god's power

was ritualised by ancients in exotic ways. In some villages in Ireland,

the womenfolk tie up strong young men with ropes, to symbolise the

nature-god's loss of power, but untie them after a while.

Lo and behold, to the utmost joy of the ancients, the ‘dead’ god

begins to stir awake in Spring. Early man greeted this new life with

joyous celebrations. In almost all new year rituals and celebrations,

this process is present - sadness followed by joy.

In Sri Lanka's New Year celebrations too, these two primordial phases

are very much present. Unfortunately, many have not been able to

penetrate this anthropological evolution. In our celebrations, we have

the Old Year and the New Year.

Neutral hour

The Old Year signifies the 'death of god'. The indigenous term

“Nonagathe” really implies the neutral hour. This is the hour when the

Nature-God is without life. In our sadness, we refrain from kindling the

hearth. We do not eat or drink. We resort to meritorious deeds and

spiritual activities.

At the end of the Old Year (at the conclusion of Nonagathe), the

“dead” God re-awakens with life. We rejoice with his new life. Hearths

are rekindled. Feasts are held. Relatives and friends exchange visits.

We begin life anew with the newly risen god. At the end of the Old Year (at the conclusion of Nonagathe), the

“dead” God re-awakens with life. We rejoice with his new life. Hearths

are rekindled. Feasts are held. Relatives and friends exchange visits.

We begin life anew with the newly risen god.

We start transactions afresh. We begin our livelihoods. The whole

meaning of the New Year celebrations will come home satisfactorily if we

appreciated the ancient roots of this wholesome celebration. The

celebration unifies the community - by making it necessary for the

entire community to initiate rituals at a stipulated moment.

Once the profound significance of the New Year celebrations is fully

understood, we can bring the people back to observe the New Year as an

important segment of our indigenous culture.

The alienation from our great cultural legacy is largely due to the

hiatus in our awareness of what the indigenous way of life could

contribute towards our enrichment.

|