‘More sandbags, police pickets in south Delhi than Jaffna’

by Swapan Dasgupta

Last week, I sent a Twitter message from the Jaffna town, which I was

visiting after 25 years. “There are more sandbags and police pickets in

south Delhi”, I observed, “than there are in Jaffna town.”

|

The Jaffna Library, a picture of old-world serenity |

This terse message, based entirely on my observation, provoked howls

of protest. Various individuals responded, denouncing me as “anti-Tamil”

and a stooge of Sri Lankan President Mahinda Rajapaksa, the latest

whipping boy of the morally indignant.

It is entirely possible that a brief 24-hour visit to a town where it

was once common to find gun-toting members of various para-military

factions walking with a swagger, does not qualify me to pass judgement

on the totality of the situation in Sri Lanka’s Northern Province.

Yet, it would be fair to say that the Jaffna I returned to was a very

different place from the strife-torn but sleepy town that existed in the

late-1980s. What I encountered was a mid-sized town with good roads and

lots of new buildings, bustling with activity. The Nallur Temple looked

as grand as ever and the Jaffna Library of which the burning in the

1980s had created so much tension, was a picture of old-world serenity.

The stadium named after Alfred Duraiappah, whose murder was among the

first of the LTTE’s ‘hits’, seemed well maintained and there is even an

Indian Consulate in place in a carefully renovated bungalow.

Yes, there were the occasional signs of the bitter battle that had

ended barely four years ago; but anyone who didn’t know that this town

was once in the frontline of one of the most ugly battles of all times

would never have guessed.

This is not to say that everything is hunky dory. At a gathering of

members of the Jaffna civil society, there were voices raised against

the acquisition of “Tamil lands” by the Sri Lankan army in its security

zone adjoining the airport. There were complaints about “Sinhala

colonisation” of areas in the southern regions of the Northern Province.

TNA MPs

And in Colombo, MPs belonging to the Tamil National Alliance

presented us (a five-member team invited by the Bandaranaike Centre for

International Studies) with a well-written account of Tamil grievances.

Its leader, the 80-year-old Rajavardayam Sampanthan, who resembles a

majestic Roman senator, both in appearance and eloquence, spoke about

the Sri Lankan Government’s underlying desire to make the Tamil people

“extinct” from the Northern and Eastern Provinces.

Yet, at a lunch hosted by businessmen of Indian origin in Colombo, I

asked a Chettiar businessman how many Tamils there are in the capital

city. “About 30 percent of the city” he replied. “And do you control 60

percent of the business?” I asked smilingly. “Only 60 percent”, he

retorted with a tinge of disappointment. “It’s more like 70 percent” he

said with a hearty laugh.

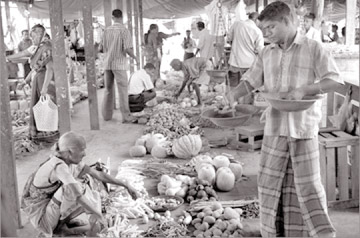

|

People of Jaffna going about their business |

Clearly, the noble Sampanthan’s theory of Tamils being an endangered

breed in Sri Lanka doesn’t have too many takers south of the Elephant

Pass.

The ‘Tamil problem’ that provides livelihood to the global human

rights industry and provokes indignation in some circles in India seems

essentially a Jaffna problem, and should be renamed as such.

At the heart of the problem is the term devolution which was

recommended to the Sri Lankan Government as a possible solution to the

problem by the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) set

up by President Rajapaksa in the aftermath of his famous military

victory over the murderous LTTE.

For India, which still takes a needlessly gratuitous interest in the

internal affairs of a sovereign neighbour, ‘devolution’ basically means

implementation of the 13th Amendment which formed a part of the

embarrassment called the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord signed by Rajiv Gandhi

and J.R. Jayewardene in 1987. This amendment promised two things: the

merger of the Northern and Eastern Provinces, the so-called Tamil

homelands, and the formation of Provincial Councils, akin to India’s

State Governments.

But two problems have arisen. First, the merger of the Northern and

Eastern Provinces was set aside by the Sri Lankan Supreme Court on

procedural grounds. Sampanthan calls it a “dishonest judgment”, but the

de-merger is now a reality. Secondly, it would seem that apart from the

Northern and Eastern Provinces, the Sinhala areas aren’t terribly

enthused by the idea of Provincial Councils. Yet, elections to the

Provincial Councils have been held in all provinces barring the Northern

Province.

Second thoughts

At one time it seemed that the Government was having second thoughts

about holding Provincial Council elections in the Northern Province, but

President Rajapaksa has categorically announced that the democratic

exercise will be undertaken in September. The TNA now says that the

powers of the Provincial Councils are inadequate. It wants the local

Government to control land and the police. The Government may concede

the first point, but there is no way it will relax its control over all

aspects of security in the North.

Who can blame Colombo for its reluctance? It’s just four years since

the LTTE was decimated and it’s just too early for the Central

Government to let down its guard. It is not that there is a desire to

militarise the province. The Sri Lankan Army is present in large numbers

in the Northern Province, but it operates well below the radar.

Logistically, the Army wants to insulate itself in the security zones,

build strategically located cantonments and operate as a rapid response

force, just in case insurgency resurfaces.

Ideally, the TNA should have no problem with this arrangement because

its members were also murderously targeted by the LTTE. Moreover, it has

declared, perhaps under Indian pressure, that it is committed to the

territorial integrity of Sri Lanka. It may still believe in emotional

separatism, but it has formally abjured political separatism and

abandoned the erstwhile TULF’s call for ‘self-determination’.

At the same time, its actions suggest that it wants to keep tensions

and the conflict alive.

It doesn’t make sense until you realise that Tamil separatist

politics derives its main impetus, not from the ordinary people of

Jaffna who are desperate for a breather, but by the Tamil diaspora, the

ones who bankroll the seemingly respectable, ‘moderate’ politicians.

With a view of the island that is frozen in time, it is the diaspora

that is proving to be the biggest impediment to Sri Lanka getting over

its troubled history.

- The Pioneer |