Evidence of liquid oceans on Saturn's moon increases chances of

finding alien life

One of the moons of Saturn has turned out to be another possible

habitat for extraterrestrial microbes after scientists have discovered

that it possesses a large ocean of water beneath its icy surface.

Measurements of gravity fluctuations around Enceladus taken by NASA's

Cassini spacecraft indicate that there is an underground ocean of melted

water at the moon's south pole which may be the source of dramatic

vapour plumes seen at its surface.

The existence of liquid water is widely assumed to be a vital

precondition for life so its presence suggests that Enceladus may be

another habitable part of the Solar System, along with Titan, the

biggest moon of Saturn, and Europa, an ice-covered moon of Jupiter.

|

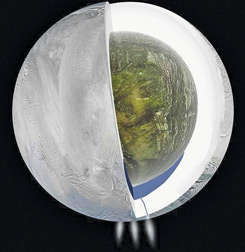

An illustration of the interior of Enceladus based on data

from Cassini, which suggests an ice outer shell and a low

density, rocky core with a regional water ocean sandwiched

in between at high southern latitudes |

A study led by Luciano Iess of Sapienza University in Rome, shows

that during three flybys of Enceladus between 2010 and 2012, which

brought Cassini within 100km (62 miles) of its surface, the spacecraft's

velocity changed slightly in response to fluctuations in the moon's

gravity field, which could only be readily explained by the presence of

a large body of liquid water at its south pole.

"Using geophysical measurements, we have been able to confirm that

there is a large ocean beneath the surface of Enceladus's south-polar

region.

This provides a possible source for the water that Cassini has seen

spewing from the geysers in this region," said Prof David Stevenson, a

co-investigator at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

"This water ocean may extend halfway or more towards the equator [of

Enceladus] in every direction.

This means that it is as large, or larger, than Lake Superior [the

largest of the Great Lakes]," Prof Stevenson said.

The Cassini spacecraft observed the water plumes on Enceladus in 2005

to the surprise of astronomers given that the surface temperatures on

the moon, which is barely 500km wide, hover around minus 180C and the

lunarscape is covered in a thick crust of solid ice.

Calculations suggest that the liquid ocean is located at a depth of

between 30km and 40km beneath the surface and is prevented from freezing

up completely by the geophysical heat generated by the tidal forces on

the moon as it completes its elliptical orbit around Saturn.

"Enceladus shows some similarity to Europa, a much larger moon of

Jupiter, which, like Enceladus has an ocean that is in contact with

underlying rock.

In this respect these two bodies are of particular interest for

understanding the presence and nature of habitable environments in our

Solar System," Prof Stevenson said.

"The data suggest that indeed there is a large, possibly regional

ocean about 50km below the surface of the south pole.

This then provides one possible story to explain why water is gushing

out of these fractures we see at the south pole," he said.

Liquid water is denser than ice - which is why ice floats on water -

and this difference in density deep under the frozen surface causes

fluctuations in the moon's gravity field, which resulted in Cassini

slowing down by a few millimetres per second as it flew past Enceladus.

Calculations suggest the ocean is 10km deep. Although there is no

direct evidence connecting the underground ocean to the surface plumes

of salty water vapour, the astronomers believe the two are connected via

a network of "tiger stripes" or fractures in the ice that can be seen

from space.

"Material from Enceladus's south polar jets contains salty water and

organic molecules, the basic chemical ingredients for life," said Linda

Spilker, the Cassini project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion

Laboratory in Pasadena.

"Their discovery expanded our view of the 'habitable zone' within our

solar system and in planetary systems of other stars.

This new validation that an ocean of water underlies the jets

furthers understanding about this intriguing environment," Dr Spilker

said.

- The Independent

|