|

Ecological sensitivity combined with die hard

frugality and a flare for style:

Ecstasy from railway sleepers

by Aditha Dissanayake

|

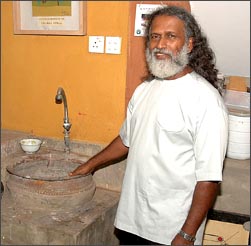

Architect Kapila Sugathadasa

|

Agrey yoke, weather beaten and old, hangs at the entrance, barely

touching the visitor's head.... with the missing sokada yet to be

brought back from Nilgala. From a jack fruit tree in the corner of the

sitting room hangs an unripe fruit left to ripen (varaka venakan), in

the days to come.

A replica of the flag used at the Uva-wellassa battle hangs on a wall

made from discarded cabok ,.... The result - a sense of serenity and

wonder which hangs throughout the surroundings, as the hostess, Namali

invites you to "sit somewhere" , (kohe hari indaganna in the absence of

chairs) while she does the week's iorning on the verandha and the host,

Professor Sarath Kotagama, just back from a day's work at the University

of Colombo, lets his hair down, and joins the conversation.

Bliss can be defined in many ways. To me, bliss is enjoying a cup of

tea seated at a table made from a discarded drum wheel, once the

property of the Ceylon Electricity Board, with a serene miniature statue

of the Buddha gazing at me from the other end of the garden, or sitting

on the lanu anda listening to the professor as he narrates the story of

his house, built with refuse ("okkoma recycle badu" ) with a smile on

his face.

A smile, which, however, would go undetected because, in this house

of refuse, the interior is dark, dark, dark. Adhering to the ways of our

ancestors who, as the Architect Kapila Sugathadasa explains, built their

houses with small dark rooms, the living area of the Professor's house

too, gets no direct sunlight.

"No sunlight means no glare and no heat which in turn means there is

no need for curtains". Explains Kapila.

|

Prof. Sarath Kotagama with the fifty-six year old koraha |

No curtains, no chairs, no plaster on the walls, no panes on the

windows and no fans or air conditioners because the house 'catches the

air draft' - here is a style of living stripped to the bare essentials.

A place where environmentalists will find utopia, the Professor says

70% to 80% of the material in his house is what others have thrown away.

"I have added another r to the three rs - refuse, reduce, recycle,

reuse, because someone has to refuse first for us to reuse the

material".

Most of the bricks, the coconut rafters on the roof, the tiles in the

bathrooms are the refuse of someone else's house. Not only does this

save earth's dwindling resources, but money as well. The entire cost for

the house was Rs. 1.7 million (in 1997). "The cost of a cabok at the

time was Rs.16. I bought what was removed from old houses for Rs.6.00"

recalls Prof. Kotagama.

Then comes the all transcending smile, brightening the semi-dark room

"But it's not easy to find a house builder (Bass) willing to work with

material bought from old houses.

Most of them refused to work with me saying the bad omens (vas dos )

attached to those houses will move into the new house too". He had

finally managed to convince one Bass by saying "I'm the one who will be

living in the house. Not you. So don't worry", a Bass who had turned out

to be obliging to a fault.

Though superstition is something the professor shrugs off as bunkum

(it does not bother him that the number of his house is 13/13 because he

sees it simply as an identification mark)in order to please his Bass he

had gone to a priest to find an auspicious time to start building the

house.

The priest had refused to state a time for the bahirava pooja because

the land was triangular. It was only after the professor had persuaded

the priest that he would make the triangular land into a rectangle by

having a gate in one corner of the land that the priest had obliged.

From this gate made out of discarded packing boxes, obtained, again

from the Ceylon Electricity Board to the railway sleepers used as

pillars, the flower vases turned into lampshades, the koraha in which

the Professor had his first bath, now a sink in the dining area, the cot

used by the two children turned into a sofa, here are evidence of how

creativity has been pushed to the limits to give a home to things which

would otherwise have ended as garbage.

Though Namali, (tongue in cheek) says people mistakenly think their

home is a pottery workshop, (mati vadapolak ) the house is a symbol of

ecological sensitivity worth emulating.

Interested in saving earth's resources? Build a house like Professor

Kotagama's. For, here is one way in which you can be the change you want

to see in the world.

[email protected] |